by Karen Cantor Paul, PhD candidate in Art History at Stony Brook University

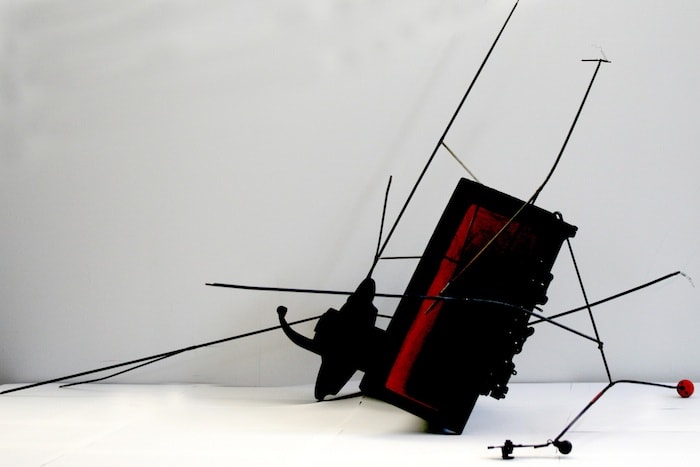

Esphyr Slobodkina’s Trophy No. 1 certainly looks like some kind of wild creature that was hunted and mounted on a wall plaque. Yet this conquered beast would have to hail from some alien planet of mechanized bug-things with its screw eyes, plastic red tongue, and metal antennae.

Like most of Slobodkina’s two and three-dimensional constructions, Trophy No. 1 is playfully ironic, combining found objects in unexpected and evocative ways. These works stand in sharp contrast to the clean lines, delineated geometries, and flat expanses of color that characterize her coolly non-objective paintings. Slobodkina’s assemblages are notable for their visual and symbolic complexity, and because hers are among the few examples of assemblage art produced in the United States during the 1930s.

The late 1920s to the early 1940s was a formative period in the development of American abstract painting and sculpture [1]. Although abstraction was not new to the American art scene, never before had artists mobilized so ambitiously to develop native interpretations of European and Russian modernist movements.

Cubism, constructivism, and surrealism provided important conceptual and aesthetic underpinnings for new explorations into abstract idioms that would gain a distinctly American character. The American Abstract Artists (AAA), formed in 1936 to “express the authenticity and autonomy of the modern movement in the United States [2],” was a driving force in these efforts, exhibiting radically non-representational art during an era in which social realism and Regionalism’s reassuring images of Americana were the dominant modes of expression.

The sculpture produced by the American Abstract Artists, of which Slobodkina was a founding member, synthesized a variety of European influences. For example, the welded abstractions of David Smith and Ibram Lassaw combined surrealist imagination with constructivist concepts of open forms, kineticism, and the use of industrial materials. Ilya Bolotowsky, Charles Shaw, and Gertrude Greene created Arp-esque relief constructions, while Burgoyne Diller’s constructivist reliefs reflected tenets of Neo-plasticism. Cubist-inspired shapes characterized the freestanding forms of George L.K. Morris, Louis Schanker, and Herzl Emanuel [3]. Slobodkina’s three-dimensional works are rooted in similar traditions, but stand apart for their use of unmasked found objects.

Slobodkina was among the few who used materials reclaimed from everyday objects, such as typewriter keys, furniture legs, dishware, hinges, motor parts, and gears, incorporating them into reliefs or fully three-dimensional constructions without disguising their quotidian origins through paint or other means. These works are of a similar spirit perhaps only to fellow AAA member Vaclav Vytcail, whose reliefs harnessed the “looser, more informal spirit of the cubist collage and assemblage or of the Merz constructions of Schwitters [4].”

Pioneered by Picasso and further developed by Dadaists such as Duchamp, Man Ray, and Kurt Schwitters, assemblage [5] and its two-dimensional cousin, collage, were already well-established modes of modernist expression by the time Slobodkina began her explorations of the techniques around 1935. Like abstract painting, the advent of assemblage provided a visual language that could address modern understandings of art, the self, and society.

As noted by Katherine Hoffman, “collage may be seen as a quintessential twentieth-century art form with multiple layers and signposts pointing to a variety of forms and realities, and to the possibility or suggestion of countless new realities [6].” The very act of fragmentation and reconstitution inherent in collage and assemblage served as an apt metaphor for the modern world where absolutes and established truths were continually being called into question by new discoveries in science, technology, and psychology.

It is likely that Slobodkina first became aware of collage and its aesthetic potential during her childhood in Russia. By 1918, when Slobodkina attended her first exhibition of modernist art at age 10 [7], Russian artists had already been experimenting with collage for about six years. Artists such as Rosanova, Goncharova, Malevich, and Popova collaborated with poets to illustrate texts and book covers, often with “brightly colored collaged papers” as early as 1912 [8]. Malevich, before developing Suprematism, executed a number of “alogical associations” – collages that combined abstract forms, words, and recognizable objects [9].

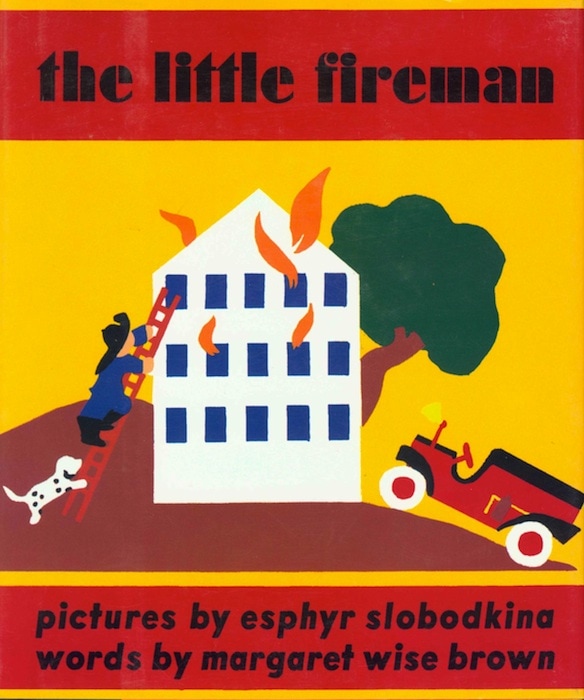

Further, when the Revolution erupted, political posters bearing a crisp, graphical collage aesthetic dominated the Russian landscape. Although it is difficult to postulate how much the Russian avant-garde directly influenced Slobodkina, her 1938 collage illustrations for Margaret Wise Brown’s The Little Fireman evokes this tradition as each page comes alive with similarly bright hues, simple shapes, and repetitious patterns. Decades after its initial publication, children’s book scholar Barbara Bader noted that “The Little Fireman in its original five brilliant, off-beat colors is perhaps the apogee of modernism in a picture book [10].”

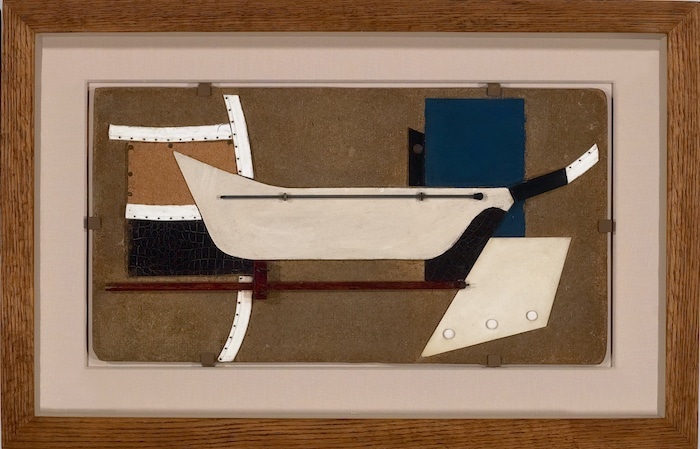

In 1935, a few years prior to the publication of The Little Fireman, Slobodkina created her first assemblages, Construction No. 3 and Boat Construction, also with roots in Russian art. In these two relief constructions, found pieces of metal, wood, and wire are affixed to canvas board in a manner that conjures Vladimir Tatlin’s “painterly reliefs” from 1913-14.

More contemporaneously, Slobodkina’s constructions relate to David Smith’s painted reliefs of the early 1930s – a mode that Smith soon abandoned in favor of welded steel forms – and Vytacil’s constructed reliefs mentioned earlier. The creation of relief constructions that utilized wood and metal elements was common among AAA artists such as Gertrude Green, Ilya Bolotowsky, Charles Shaw, and Burgoyne Diller, but Slobodkina’s works were visually quite different from those of her colleagues. For example, in Greene’s Construction in Blue (1937), each smoothly shaped wooden attachment blends almost seamlessly with the painted canvas upon which they float. These are not found objects but carefully shaped sculptural forms that serve a purely aesthetic purpose.

By contrast, the objects in Slobodkina’s Construction No. 3 are rough and unrefined, betraying their origins as scrap. Rather than hover atop the canvas, her forms are clearly bolted down by visible nails and screws. In true assemblage fashion, Slobodkina uses found objects not strictly for their formal shapes and colors, but for their unique textures and myriad associations.

The introduction of assemblage art to the United States can be traced to around 1915 when New York Dada, associated with Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Man Ray, was an influential force. In 1917, when Duchamp exhibited his infamous Fountain (in fact a shiny porcelain urinal), this radical move challenged tenets of acceptable art practices and materials and paved the way for further experimentation.

As observed by Jeffrey Wechsler, “the Dada presence in American added immeasurably to the atmosphere of experimentation which inspired many of this country’s first-generation modernists [11].” Suddenly, it was okay for any object, regardless of how prosaic its origin, to be used in the context of fine art. However, outside of Duchamp and Man Ray, few artists working in the United States adopted the practices of collage and assemblage, at least initially. Dickran Tashjian asserts that “except for Man Ray, American Artists generally neglected assemblage during the early phase of modernism after the Armory show [12].”

Among those who did explore assemblage in the 1920s were Arthur Dove, Joseph Stella, and John Covert. But it was not until the mid 1940s and into the 1950s and 60s that assemblage became more widely practiced by artists such as Louise Nevelson, Lee Bontecou, Richard Stankiewicz, Mark di Suvero, and John Chamberlain. Slobodkina’s assemblages of the mid to late 30’s thus offer one of the rare links between New York Dada and later assemblage art.

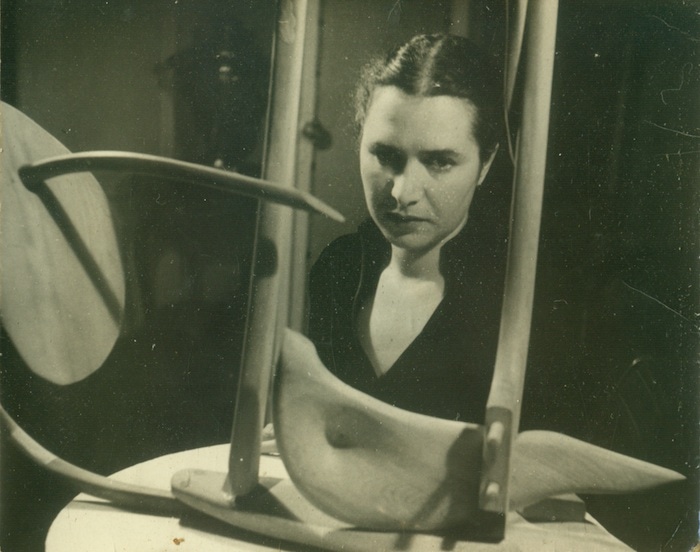

Around 1938, Slobodkina produced two of her finest assemblage works, Tabletop Gazelle (originally named Synthesis) and The Derelict, both constructed from parts of a vintage standing mirror that Slobodkina found in a secondhand shop. Deconstructing the antique, Slobodkina used the mirror to complete a makeshift dressing table that furnished her 60th street Manhattan apartment, and, not letting anything go to waste, refashioned the leftover stand into these artworks [13]. Also incorporated into both pieces are parts of a disassembled Windsor chair. For each, the result is an elegant composition of abstract shapes and innovative spatial relationships.

Like fellow AAA members David Smith and Ibram Lassaw, Slobodkina demonstrates a concern for creating open forms as opposed to the closed masses of more traditional sculptural works. In addition to her formalist concerns, these works conjure imaginative associations that relate to Surrealist practices of unexpected juxtapositions and evocation of the unconscious.

Indeed, Slobodkina discussed The Derelict in terms of “subconscious Surrealist association [14].” This work “was related to a Russian song she had learned in her youth; the poetic lyrics describe gray, derelict ships in a frozen sea [15].” Also like many Surrealist works, The Derelict synthesizes seemingly opposing visual motifs: it’s both melancholy and serene, full of symbolic allusions yet ostensibly non-objective.

While Slobodkina’s approach to painting is painstaking and methodical, entailing a number of preliminary pencil and oil sketches and the use of a transfer grid, her assemblage art is composed in a more improvisational, spontaneous manner. Like many Surrealist and Dada approaches to art-making, Slobodkina relied on elements of chance and serendipity when working in three-dimensions. As Elizabeth Wylie has noted, Slobodkina “works in a direct way, making her sculptures out of found objects that trigger associations for the artist as she constructs them [16].” Slobodkina echoes this conclusion in talking about her 1938 piece, Sailor’s Wife:

There used to be some kind of crazy hanger for trousers… Anyway this looked like an anchor so I used this and an embroidery hoop and a darning egg and strings, so I mounted the whole thing and it began to look like a sailor’s wife at home doing the darning and sewing and embroidery, and may be associated with her waiting for the return of her man. That’s where those titles come from…I never set out to make a sailor’s wife – it would ruin everything. It’s more like a writing process. Writers don’t know what they’re going to write, it comes out in the writing [17].

Objects associated with needle craft again appear in Thrust No. 1, 1947. One of Slobodkina’s more aggressive works, Thrust transfigures normally benign objects into a threatening weapon as weaving shuttles and thick, industrial-sized needles comprise a deadly catapult of sorts. One is reminded of Man Ray’s 1921 Gift where a simple flatiron is made menacing by the addition of sharp, teeth-like tacks. In both, the functions of utilitarian objects have been cleverly subverted, challenging viewer expectations and echoing William Seitz’s observation that “Dada awakened senses and sensibilities to the immense multiple collision of values, forms, and effects among which we live, and to the dialectic of creation and destruction, affirmation and negation, by which life and art progress [18].”

It is thus through Slobodkina’s assemblage that one can gain a sense of her wit and unfettered imagination. And although grounded in abstract principles of composition practiced by the AAA, Slobodkina’s constructions stand apart for their unconscious associations and provocative juxtapositions.

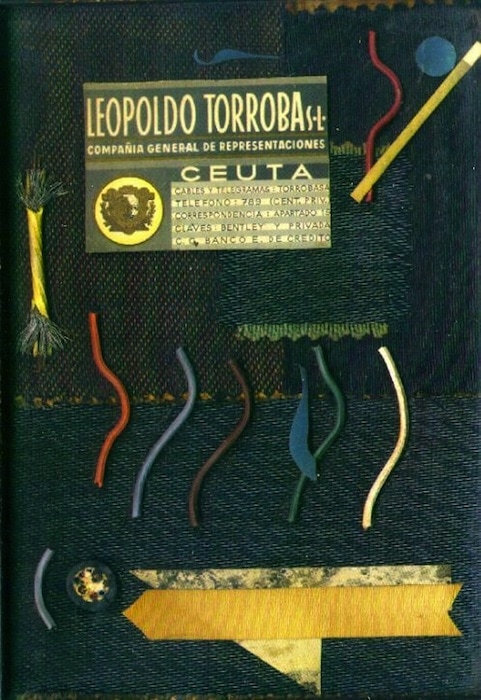

In addition to her three-dimensional assemblages, Slobodkina created a number of collages, including a notable series from 1948 that includes Crossroads, Shopping Industry and The Spangles. Each one, composed while working in the office of her second husband, William Urquhart, incorporates the unremarkable flotsam of workaday life: used papers, stamps, envelopes, bills, and product packaging. In discussing Crossroads, Slobodkina recalls:

This is a tiny little thing with the old-fashioned telephone sign…I did those between doing my bookkeeping and answering phones and doing everything else in the office. I was really working the materials that came across my desk. These were old fashioned telephone bills with these blue telephones…I use anything I feel like [19].

Slobodkina’s temerity to “use anything” as artistic media evidences her bold, individualistic spirit. However, she also owes a debt of gratitude to Dada artist Kurt Schwitters and his influential Merz pictures of the 1920s that pioneered the use of everyday junk – “streetcar tickets, cloakroom checks, bits of wood, wire twine, bent wheels, tissue paper, tin cans, chips of glass, etc [20]”– as fertile material for collages. In elevating daily detritus to the realm fine art, Schwitters and Slobodkina call attention to the throw-away nature of consumer culture. Whether this evocation is celebratory or critical remains ambiguous, left for the viewer to decide.

Throughout the fifties, Slobodkina focused mostly on painting. However, in the sixties, when “junk” art became more widely practiced by artists such as John Chamberlain, Slobodkina returned to assemblage more avidly. Like Chamberlain, Slobodkina created works that reflect an interest in mechanical objects, but while Chamberlain’s crushed car bodies have a critical edge, Slobodkina’s constructions are more lighthearted and playful.

Escape No. 1, 1960, resembles a dead or dying giant insect, its weighty body an industrial-sized metal horn culled from a commercial alarm system and its spindly legs pieces of radio antennae. While this machinated bug fails its escape attempt, a related work, Escape No. 2, 1960, looks like it might succeed. Like a boat out of a surrealist dreamscape, with a sail made from the top half of a fan cover, a sturdy metal hull from some unidentified machinery, and rigging from painted black string, this fantastic dinghy seems about to float away.

Another work from this period, Typewriter Bird, 1960-1, is the first of several assemblages using antique typewriter parts. Slobodkina recalls, “I found an old typewriter in the corner and couldn’t use it because it was broken so I made something out of it [21].” Here, typebars are arranged like plumage around the carriage as several typewriter keys, with their finger-sized round tips, accentuate the display. All three works belie Slobodkina’s lifelong fascination with mechanized things and her belief that even outmoded technologies can be put to good use.

The eighties marked a creative renaissance for Slobodkina, who constructed some of her most provocative assemblages during this decade. More so than earlier works, these possess a wry, satirical edge and demonstrate an active engagement with contemporaneous social issues and political concerns. For example, Our Great Big Happy Condominium in the Sky, made in 1988, visualizes how humans might reside in the future should space colonization become a reality. The compact, rocket-shaped abode is constructed from wooden weaving shuttlecocks anchored into a metal base made from a five-stud trailer hub. Slobodkina’s prescience is at once amusing – these obviously phallic structures are, after all, ridiculous – but not unimaginable. Her keen ability to illuminate the thin line between reality and the absurd contributes to the success of this work.

Within the Mysterious Parameters of Privileged Information, also from 1988, synthesizes the diverse influences that have informed Slobodkina’s work to date. It immediately conjures Vladimir Tatlin’s constructivist maquette, Monument to the Third International, 1919-20, but with an absurdist, Dada twist. Here, Tatlin’s architectural spiral has been replaced by interlocking teethed discs. They enclose a white furniture leg crowned by a red wheel caster that stands tall in a mockery of a patriotic symbol – like an emasculated Washington Monument. The discs bear the inscription, in red, “within the mysterious parameters of privileged information.”

According to Slobodkina, the work was inspired by media coverage of the Iran-Contra hearings. Annoyed by the dissembling nature of political speech, especially the overuse of ambiguous terms like “privileged information” and “parameters,” she created this non-monument as a critical response to political doublespeak. Slobodkina explains that “on the bottom is written the definition of parameter. That explains why it is such an absurdity because actually they can’t be within parameters because the parameter itself is a changeable entity so there is no such thing as within the parameters of anything [22].”

In another socially conscious work, Slobodkina offers a subtle critique of the educational system. Her Sadly Sagging Educational Spiral, 1988, brings together a typewriter spring, fan cover, and an automobile “U” joint. These disparate manufactured parts are reassembled to form a new apparatus that appears capable of locomotion. The irony is that this machine would likely travel only in circles, never making any forward progress.

A more personal piece, The Broken Promise of Marital Bliss, 1989, alludes to Slobodkina’s failed first marriage to artist Ilya Bolotowksy (the two married in 1933 and were separated by 1936), but in a humorous rather than wistful or melancholy manner. Slobodkina arranges the candy cane-shaped scrolls of a bentwood chair, probably chosen for their graceful curves resembling fiddleheads, so that they oppose each other. Attached are smashed pieces of ceramic dishware – perhaps a reference to inevitable domestic disputes. A broken egg cup serves as the central pivot around which the sinuous scrolls warily regard each other like spouses on the verge of estrangement. Not even the strong gravitational pull of domestic responsibility can hold this metaphoric couple together. The presence of a third scroll suggests an adulterer also plays a role in this visual fable of marital life.

Trophy No. 1, cited at the beginning of this essay, and its companion, Trophy No. 2, are part of a series that Slobodkina referred to as GIOSO, or Great Ideas of Small Origins. In coining this moniker, Slobodkina states a fundamental concept that has informed her assemblage art since the 1930s: that any object or material, no matter how mundane, can serve as the starting point for great works of art. She would refer to the same works as being part of her “Destroy and Search” series. An inverse of the military slogan “Search and Destroy,” the phrase refers to Slobodkina’s tactic of deconstructing household objects and discovering new ways to reconfigure their parts into artworks [23].

Trophy No. 1 and Trophy No. 2 are both wall mounted constructions that combine typewriter parts with copper printing plates that were used for the production of AAA catalogs. In fact, one can see trace outlines of old designs permanently ghosted into the plates [24].

These are perhaps Slobodkina’s most fantastical assemblages, and, according to one critic, “could be straight out of David Cronenberg’s film version of Naked Lunch [25].” Slobodkina returned to the series in 1998 with Thrust Trophy No. 3. Although using similar materials, including typewriter parts and copper plates, this construction is less bug-like. Instead, it more closely resembles the face of a 19th century camera. Where the lens would be is a circular opening through which a metal tongue protrudes. Spindly metal elements add a touch of anthropomorphism to this unusual relic.

Slobodkina continued to produce three-dimensional constructions until about a year before her death. In fact, her last completed work, Ahead with Fair Winds No. 2, 2001, is an assemblage. In this piece, Slobodkina used more recognizably contemporary materials, including Formica, a computer fan, and a CPU casing. Made at age 93, this late piece testifies to Slobodkina’s singular artistry and tireless spirit. Her keen sense of abstract composition and her fearless conviction to “use anything” are qualities that distinguished Slobodkina’s 1930s assemblage art and that will attest to her enduring legacy.

About the Author

Mrs. Cantor Paul received her Masters in Art History and Criticism at Stony Brook University and Archives and Collections Director at the Slobodkina Foundation.

Endnotes

1 In the catalog Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America 1927-1944 (Pittsburgh: Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1983), editors John R. Lane and Susan C. Larsen suggest that this period marks a “revitalization” of the abstract tradition in the United States. In 1927 Stuart Davis began his “Eggbeater” series and A.E. Gallatin opened the Museum of Living Art and by 1944 – the year of Mondrian’s death – abstract expression had gained international currency as the new modernist style.

2 Quoted from the American Abstract Artists second annual exhibition catalog. Available through the Archives of American Art, Roll N459-11, Frames 193-207.

3 For examples of sculptural works during this period, see Joan Marter, “Developments in American Abstract Sculpture During the 1930s,” in Vanguard American Sculpture 1913-1939, Joan M. Marter, Roberta K. Tarbell, and Jeffrey Wechsler, ed. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1979), 199-140; Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, American Women Sculptors: A History of Women Working in Three Dimensions (Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1990); Joan Marter, “Constructivism in America,” Arts Magazine 51 (June 1982): 73; and Andrew P. Spahr, Abstract Sculpture in America 1930-70 (New York: American Federation of Arts, 1991).

4 Lane and Larsen, 232.

5 Following William Seitz, “assemblage” is used as broad concept encompassing various forms of composite art, including both 2- and 3-dimensional works. I also use the term to describe specifically 3-dimensional works. See William Seitz, The Art of Assemblage (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961).

6 Katherine Hoffman, editor. Collage: Critical Views (Ann Arbor and London: UMI Research Press, 1989), 1.

7 In her autobiography, Slobodkina recalls the profound impact of seeing a David Burliuk exhibition in Ufa in 1918. She remembers how his “huge canvases, mostly depicting fractured nudes and still lifes, screamed from the walls of the exhibition hall in every color known to human eye.” See Esphyr Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, Volume I (Great Neck, New York: Slobodkina-Urquhart, 1976), 80.

8 Hoffman, 9.

9 Ibid.

10 Barbara Bader, “A Lien on the Art World.” Sun, November 16, 1980.

11 Jeffrey Wechsler, “Dada, Surrealism, and Organic Form,” in Vanguard American Sculpture 1913-1939, Joan M. Marter, Roberta K. Tarbell, and Jeffrey Wechsler ed. (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1979), 67-84, p. 67.

12 Dickran Tashjian, Skyscraper Primitives: Dada and the American Avant-Garde 1910-1925 (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1975).

13 Esphyr Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, Volume II (Great Neck, New York: Urquhart-Slobodkina, 1976), 462.

14 Slobodkina quoted in Elizabeth Wylie, “The Sculpture of Esphyr Slobodkina,” in Gail Stavitsky and Elizabeth Wylie, The Life and Art of Esphyr Slobodkina (Medford, Massachussetts: Tufts University Art Gallery, 1992), 43.

15 Wylie, 43.

16 Ibid., 42.

17 Slobodkina quoted in Wylie, 42.

18 Seitz, 38.

19 Slobodkina Interview, March 26, 1991, Tape II, Side I. Transcript available through the Slobodkina Foundation, Glen Head, New York.

20 Scwhitters quoted in Hoffman, 14.

21 Slobodkina Interview, March 26, 1991, Tape III, Side I. Transcript available through the Slobodkina Foundation, Glen Head, New York.

22 Slobodkina Interview, March 26, 1991, Tape III, Side I. Transcript available through the Slobodkina Foundation, Glen Head, New York.

23 Wylie, 45.

24 Ibid., 46.

25 Cate McQuaid, “Esphyr Slobodkina Turns Geometry into Art,” Boston Phoenix, February 7, 1992.