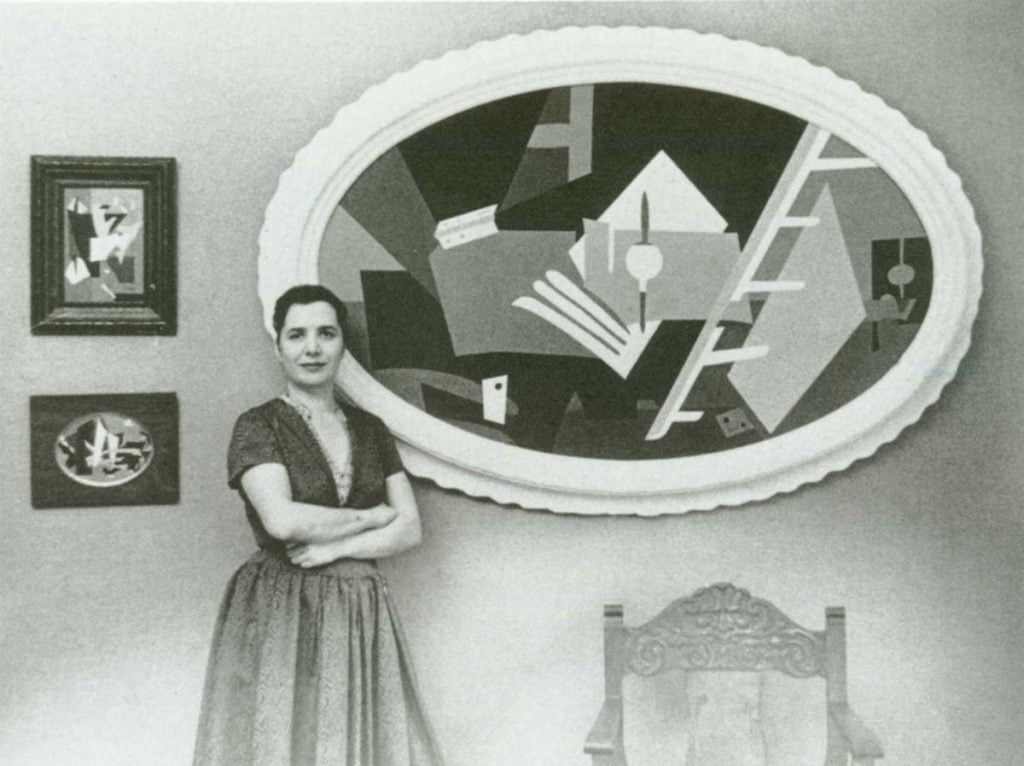

by Sandra Kraskin, PhD, Former Director of Baruch’s Sidney Mishkin Gallery 1989-2018

Introduction

Esphyr Slobodkina was a pioneer of American abstract art. In the 1930s and early 1940s, she helped to translate the work of the European modernists into an American idiom. Like her colleagues, she joined the Artists’ Union, the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP), and the American Abstract Artists (AAA) group. As an advocate of abstract art, she participated in the avant-garde activities and exhibitions that helped to achieve recognition for abstract art in the United States before World War II.

Exceptionally inventive, Slobodkina focused on painting in the 1930s and 1940s, but she also applied her talent to many areas, from writing and illustrating children’s books—her acclaimed book Caps for Sale was published in 1940—to constructing sculpture from found objects. She designed buildings, murals, decorative arts, and even textiles and couture clothing.

Strong willed and independent, Slobodkina rejected Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s, calling it “the drip, splash, and smudge school.1” She continued on her own path, although Abstract Expressionism dominated American art throughout the decade. Later, with the development of hard-edge painting during the 1960s and the 1970s, she was among the artists who were viewed as early forerunners of this movement.

Slobodkina was rediscovered as a pioneer of American abstract art in the 1980s, and her paintings were exhibited in the landmark show Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927-1944, which opened in 1983 at the Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, in Pittsburgh and traveled to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City in 1984 2. During the 1980s and the 1990s, her work was increasingly recognized, acquired by important collectors, and exhibited in major museums 3. This essay redefines her role in American art, documenting the importance of her early contributions, her later development, and the recognition she received in the last decade of her life 4.

From Siberia to New York City

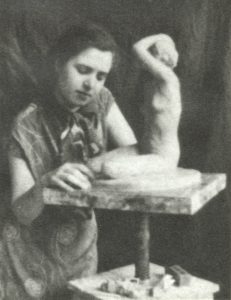

Born in Chelyabinsk, Siberia, on September 22, 1908, Esphyr Slobodkina was the daughter of the manager of a MAZUT oil branch 5. Displaced during the civil war that followed the Bolshevik Revolution, Esphyr left Russia with her mother and sister Tamara in 1920. Traveling on the Trans-Siberian Railroad, they followed other prosperous Russians to Harbin, Manchuria, where her mother established a dressmaking salon. In 1922, they were joined by the rest of the family. Planning to become an architect, Esphyr attended a preparatory school for engineering and architectural programs, where her studies included mechanical drawing. She had learned to paint from a private tutor, the Impressionist painter Pavel Goost 6. Her painting Park Bench in Harbin, c. 1927, shows her ability to create the small, quickly painted brush strokes and reflected light characteristic of Impressionism.

After graduating from the First Harbin Public Commercial School, Slobodkina decided to leave Harbin and join her brother Ronya, who had immigrated to the United States in 1923. In 1928, Esphyr, with a student visa, traveled to New York City to study art.

Heckscher Museum of Art, Gift of the Artist (1997.012.004)

Made for Arthur Sinclair Covey’s composition class at the National Academy of Design. In this homage to Russian folk art, a decorative border frames a Parthenaic procession of flat, boldly-outlined peasant figures in traditional garb.

The National Academy of Design

From 1928 to 1933, Slobodkina studied at the National Academy of Design. Both she and her sister Tamara (who also attended the academy) hated “every minute of its stupefying, senseless, destructive method of ‘teaching’ art 7.” Slobodkina qualified her judgment of the academy by making an exception for Arthur Sinclair Covey’s composition class: “We both loved Mr. Covey, and as we learned his particular method of picture organization, he appreciated our work 8.”

Slobodkina had noticed the work of another student, Ilya Bolotowsky, displayed in her composition class 9, but she didn’t meet this young artist until 1931, after he had finished his studies at the academy. The two artists were introduced by his sister, Myrrah Bolotowsky, who also studied at the National Academy.

Heckscher Museum of Art, Gift of the Artist (1997.012.012)

Like Slobodkina, Ilya Bolotowsky was a Russian immigrant, but he had arrived in New York City in 1923, five years before Slobodkina. Attending the National Academy of Design from 1924 until 1930, Bolotowsky studied primarily with Ivan Olinsky, who taught life drawing classes. However, he agreed with Slobodkina’s assessment of the National Academy:

“I always thought it was a very bad school. Now, as I look back on it, it had some advantages. The teachers were extremely academic, although Olinsky was not; he was sort of a modernist . . . We were warned not to follow people like Picasso, Cézanne and such like because Picasso never learned how to draw and Cézanne never learned how to paint, and other advice of this nature 10.”

The Walking Encyclopedia

To complete his education, Bolotowsky traveled to Europe to study the work of the old masters and the European modernists. When he returned in October 1932, he visited Esphyr and showed her reproductions of the paintings that he had seen 11. Intrigued with his knowledge, she concluded that “Here, at last, was a concrete chance to really learn something about the technique, the meaning, the history of painting. . . . Here in this walking encyclopedia of carefully selected, highly pertinent knowledge lay the solution to my quest for pure knowledge, for practical information, for plain, human encouragement 12.”

Frustrated with the academic program at the National Academy, she asked Bolotowsky if he would teach her how to paint 13. Beginning with a lecture on composition, Bolotowsky became her mentor. He stressed the organization of a painting—its form, color, and space—and illustrated his points with examples from old masters as well as modern artists 14. The following week, he was impressed to see that she had understood his lesson and produced a painting 15.

Slobodkina and Bolotowsky developed a close personal and professional relationship as they discussed art, visited other artists, and went to see many exhibitions. Visiting Bolotowsky’s friends, like the painter Byron Browne (then known as George Brown), Slobodkina learned both practical and theoretical information. She heard advice about art materials, comparisons of the work of Gauguin and van Gogh, and discussions of Picasso’s various styles as well as Cézanne’s method of building form with small brush strokes and Matisse’s use of line and color 16.

Slobodkina remembered these social evenings: “For me it was all heady, new stuff. I spent entire evenings without once uttering a word, except to say thank you when handed a cup of tea with a piece of cake 17.” She noted that “everybody was still learning from the Masters” and “by . . . keeping my mouth tightly shut, my eyes wide open, and my ears thoroughly attuned to every bit of information which came my way, I managed to learn a great deal in a very short time 18.”

Esphyr and Ilya spent the summer of 1933 on a farm near High Bridge, New Jersey, with the Bolotowsky family. During the summer, she and Bolotowsky “prepared canvasses, we ground our own paint, and we painted everything, and everybody around us 19.” When Esphyr painted the interior of her bedroom, Ilya stood in front of this painting and said, “Hm . . .,” but nothing more 20.

“Now You Can Call Yourself an Artist”

By the end of the summer, they were married. Although she had hesitated to give up her “freedom,” Bolotowsky had pointed out the practical advantages of formalizing their relationship: she could legalize her presence in the United States, become a citizen, and quit attending the National Academy of Design 21. As a woman, Slobodkina had, in fact, chosen a traditional method of becoming an artist: she learned her profession from her husband 22.

In 1934 – probably when Esphyr and Ilya were on vacation in Noank, Connecticut – she painted a still life with buttercups 23. Bolotowsky was impressed with her progress and declared, “Now you can call yourself an artist 24.” Considering her education complete, Slobodkina noted that “Never again did he give me any advice or criticize my paintings 25.”

Heckscher Museum of Art, Gift of the Artist (1997.012.007)

Yaddo Artist Colony

In the autumn of 1934, Slobodkina and Bolotowsky were both awarded Yaddo Foundation Fellowships, which provided room, board, and studio space at Saratoga Springs, New York, for artists, writers, and composers 26. At Yaddo, Bolotowsky experimented with several different styles, painting realistic landscapes and semi-abstractions. He even tried rudimentary abstraction 27.

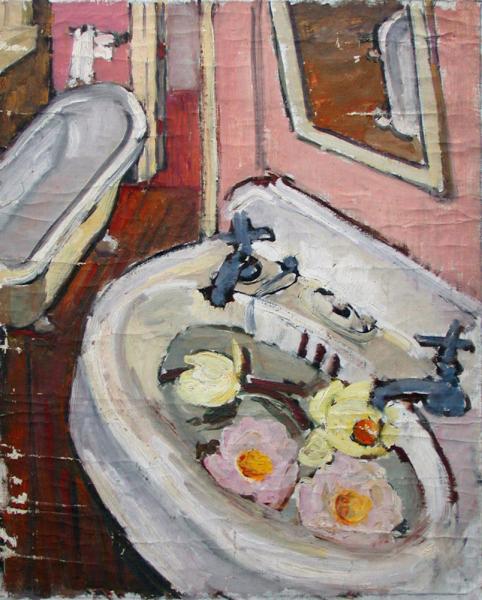

Slobodkina, preferring interiors, chose to paint the studio stove, a still life with water lilies, a bathroom with water lilies floating in the sink, and John Cheever’s Yaddo studio. These paintings reflect her exploration of Post-Impressionism: her painting of the bathroom, with its intense colors and distorted perspective, recalls Vincent van Gogh’s painting of his bedroom in Arles 28.

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Heckscher Museum of Art, Gift of the Artist (1997.012.009)

Challenged by Cubism

During the 1930s, most young, American modernists were challenged by Cubism, especially the work of Pablo Picasso, who with his colleague Georges Braque, had analyzed “nature” and restructured the “reality” of the painted surface. Bolotowsky undoubtedly took Slobodkina to see European and American modernism at Albert E. Gallatin’s Gallery of Living Art, which had opened at New York University in 1927 29. By 1933, when he was tutoring her, the collection of the Gallery of Living Art had grown large enough to present a selection of art from Cézanne up to Cubism, Constructivism, and De Stijl 30. The examples of Cubism in Gallatin’s collection in 1933 provided a comprehensive survey for artists to study 31.

Slobodkina, too, experimented with Cubism, particularly the work of Juan Gris 32. Slobodkina would have seen Gris’s painting when she first visited Gallatin’s gallery. Juan Gris’s work, in fact, had appeared in the inaugural exhibition of the Gallery of Living Art in 1927, and although he was already a well-known artist, this was Gris’s “debut in an American museum 33.”

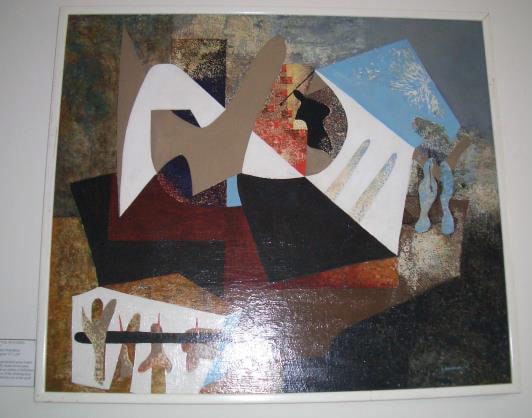

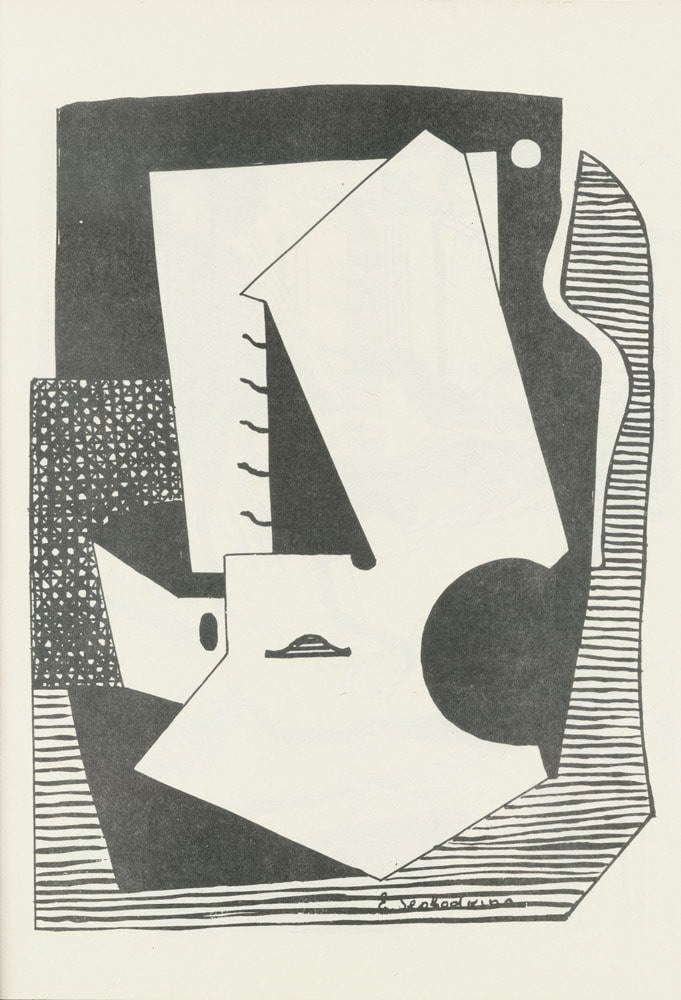

Hillwood Art Museum, Long Island University.

This cubist-inspired composition reflects Slobodkina’s growing interest in artists such as Juan Gris.

Heckscher Museum of Art, Gift of the Artist (1997.012.013)

Slobodkina described her first Cubist painting, The Sink, c. 1935, as a “fractured image of the sink in the little Clifton New Jersey bathroom. It was quite a breakthrough for me, on my own 34.” Slobodkina found that Juan Gris’s visual analysis of an object was easy to understand:

The planes he stacks one behind the other are a perfect illustration of the so-called “harmonical space”. The circles he places at the spot where the top or the bottom of a bottle or of a wine glass should be go right along with the theory of enclosure of the space which is presumably occupied by the object. The simultaneous showing of the front, profile, and the back of the object is practically the de rigueur feature of every self-respecting cubist painting, collage, drawing or sculpture, expressing the idea that an object should be viewed not only from one position, but so to speak, “in the round 35.”

Slobodkina understood how to learn from the masters, but she also knew that originality was essential: “It took great men like Braque and Picasso first to make the rules, and then calmly proceed with the breaking of them for the sake of a more effective work of art 36.”

By the summer of 1935, Slobodkina noted, she and Bolotowsky “were both experimenting with abstractions—he with the pure, non-objective type, I with the gradually freer and freer interpretation of the Cubist theory 37.”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Clarence Y. Palitz Jr. Gift, 1985. (1985.30.2)

Slobodkina’s painting The Pot-Bellied Stove, 1935, clearly represents her understanding of Cubism: the simplified, overlapping planes of the object; the circles indicating its top and bottom; and the simultaneous presentation of its front, side, and back. In this painting, she analyzed, deconstructed, and then reassembled the stove.

The American Avant-Garde in the 1930s: the Artists’ Union, the WPA/FAP, and the AAA

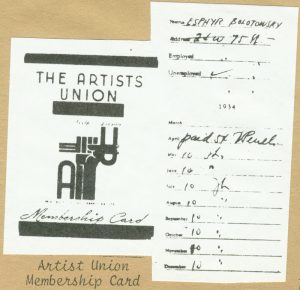

During the mid-1930s, at the height of the Depression, Slobodkina joined the Artists’ Union, she was employed by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (WPA/FAP) 38, and she participated in the avant-garde activities of the American Abstract Artists (AAA) group.

In 1934 she became an active member of the Artists’ Union, attending political rallies and picketing to create and protect government-supported jobs for artists 39.

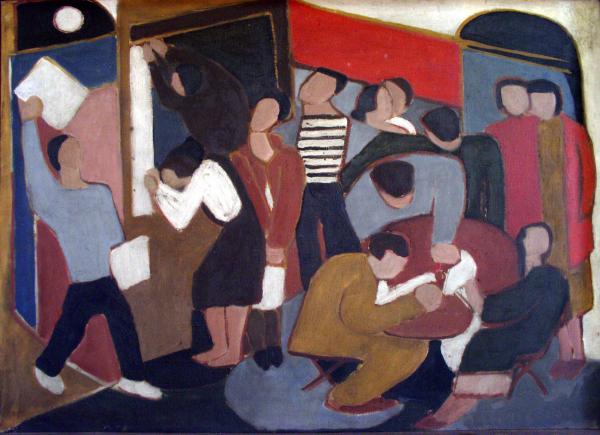

She also made posters, decorations, and costumes for special events, and she exhibited in group-sponsored exhibitions. Her 1936 painting The Angelo Herndon Petition 40 was praised by Emily Genauer in the New York World-Telegram:

Esphyr Bolotowsky . . . is earnestly struggling to get at something, and in the near-abstraction labeled “The Angelo Herndon Petition” she nearly arrives. The thing is still disjointed. But there are elements like the vertical use of reds in the design, the red banner overhead serving to unify the canvas, and the tensions and repetition of certain motifs, which definitely indicate an attempt to achieve plastically ordered form 41.

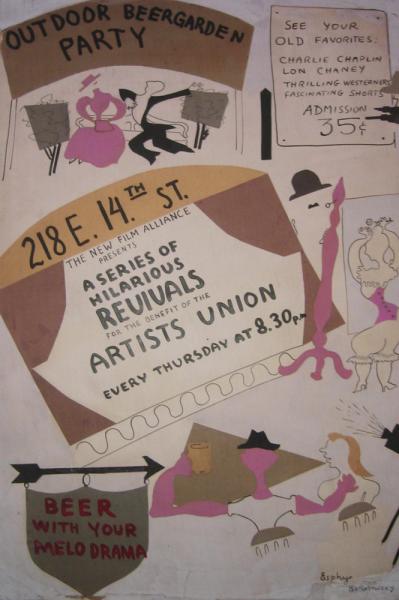

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

A poster created for an Artists’ Union fundraising event. In her autobiography, Slobodkina recalls that the benefit “consisted of showing a very old movie of the Perils of Pauline type, plus a glass of free beer. The price of admission to the little backyard garden restaurant where the whole thing was to take place, was something like a quarter or thirty-five cents.”

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Probably a sketch for costumes or decorative drawings for the “Mad Arts Ball,” another Artists’ Union event.

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Established during the Depression as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s efforts to combat unemployment, the WPA/FAP included artists in a nationwide federal relief program. Because the WPA/FAP did not allow married artists to work in the program at the same time, Slobodkina—who was separated from her husband by the summer of 1936—registered for Home Relief in her maiden name 42. When she was hired by the WPA/FAP, she was assigned to assist the artist Hananiah Harari. However, she came to his studio only to sign in; he preferred to work alone.

By 1938, Slobodkina had produced five mural sketches. Describing her sketches, she explained that “the idea . . . was to create . . . a continuous chain of interlocking shapes to produce an effect of a single unit 43.” The paintings of Joan Miró also influenced her mural sketches, freeing her “from the obligation of being completely flat and completely geometric 44.”

Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida, Gainesville; Museum purchase, funds provided by the Caroline Julier and James G. Richardson Art Acquisition Fund

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Although Slobodkina and Bolotowsky were divorced in 1938, they continued their relationship as colleagues and friends for another decade. His 1936–1937 mural studies for the Williamsburg Housing Project served as a model for her own mural sketches. With a combination of biomorphic and geometric forms and converging, diagonal lines, her sketches dated approximately 1938 recall Bolotowsky’s mural as well as the work of Miró. She later recalled, “As at that time I was still very close . . . with Ilya, I . . . suspect that his endless chatter about an ideal design he hoped to produce for his mural had some influence on my composition 45.”

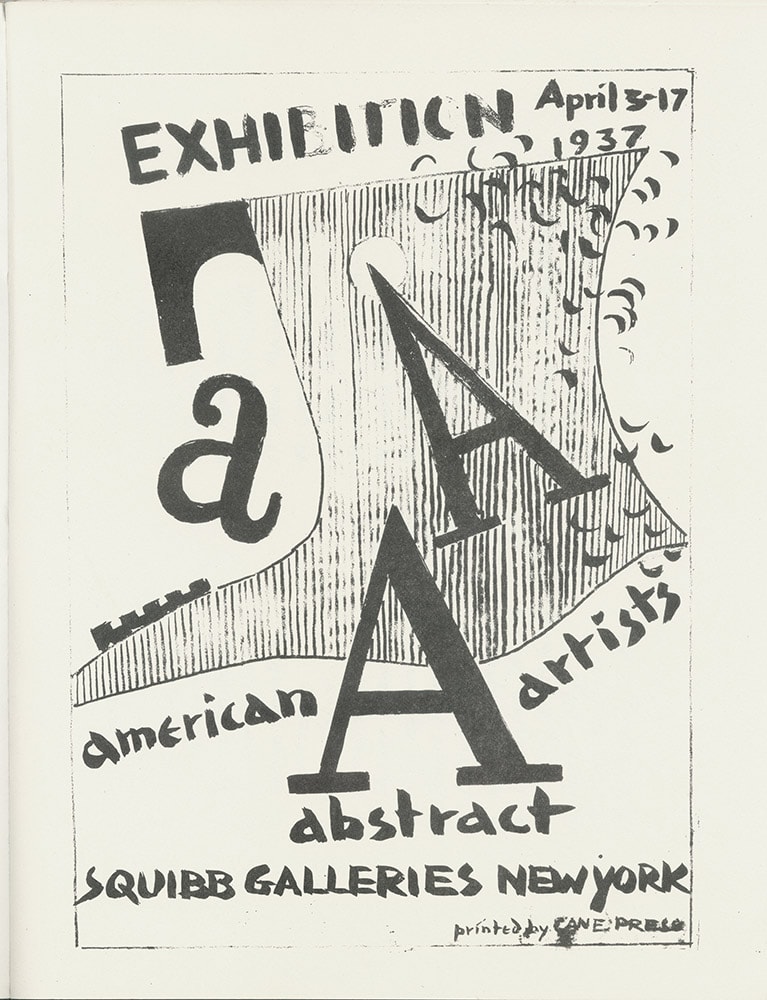

The discussions among abstract artists who worked on the WPA/FAP continued informally at the studio of sculptor Ibram Lassaw and then led to the formation of the American Abstract Artists group in 1936. Ilya Bolotowsky and Esphyr Slobodkina attended an early meeting of the new organization at Harry Holtzman’s studio in November 1936 46. Bolotowsky advised Slobodkina to join the group. They both became charter members 47 and participated in its first exhibition at the Squibb Gallery in New York City in April 1937.

Slobodkina exhibited two Cubist paintings in the first AAA exhibition—Still Life with Chair and The Pot-Bellied Stove—both dazzling works with simplified forms and bold colors 48. Slobodkina also created a lithograph on a zinc plate for the portfolio that 30 of the group’s 39 members printed to document their exhibition (Untitled, American Abstract Artists Portfolio, 1937, Lithograph, 12″ x 9¼”).

With its flat planes and circular forms, her print was closely related to her painting The Pot-Bellied Stove; although in the black-and-white print, she used parallel lines and cross-hatching to create tone. When Bolotowsky saw her print, he exclaimed, “I cannot understand how you do it! Whatever you undertake, you do it completely professionally, even if it is for the first time you touch it! 49”

Fighting for Abstract Art in the 1930s

Although more than 1,500 viewers attended the first AAA exhibition generating public attention 50, the show was attacked by critics. In the 1930s, most curators and art critics considered the work of American abstract artists too derivative of European styles of painting. Some conservative critics even concluded that art influenced by European artists was “un-American” 51; other critics dismissed all abstract art as merely decorative 52. The Depression and other economic and political events of the late 1920s and early 1930s had turned the attention of the art establishment away from modernism toward a new regionalism, fostering an interest in art that celebrated the American experience.

In a review of the first AAA exhibition, New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell attacked the quality of the show, dismissing abstract work as a “mass demonstration of decorative design 53.” However, despite negative opinions about abstract art, some artists did receive limited praise. Jerome Klein, in a New York Post review, noted Slobodkina’s paintings, including them among “some of the most interesting” work in the show 54.

Nevertheless, Jerome Klein also used sarcasm to criticize abstract art: he titled his review of the 1938 AAA exhibition “Plenty of Duds Found in Abstract Art Show.” His advice to the viewer revealed his scorn: “Very well, poke among the droppings of modern art, pick yourself a dry bone and suck on it. See what you get 55.”

The next year, in 1939, Edward Alden Jewell was even more critical; he made no attempt to hide his hostility to abstract art. In his review of the AAA show at the Riverside Museum, he concluded that “when they do not perhaps exactly exalt, they make their little decorative dingbats turn the very neatest of handsprings 56.”

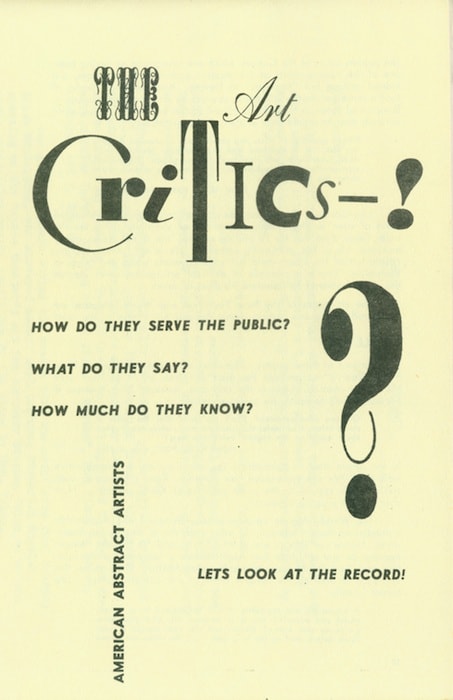

Challenging these critics in a battle that would help prepare the way for the success of Abstract Expressionism after World War II, the AAA served as a forum for the debate about abstract art. When its group exhibitions became targets for the most vicious criticism, members fought back by publishing pamphlets and catalogs that defended abstract art. They produced a twelve-page pamphlet that criticized prominent art critics: The Art Critics—! How Do They Serve the Public? What Do They Say? How Much Do They Know? Let’s Look at the Record!

This pamphlet was handed out at the AAA’s annual exhibition in June 1940. It quoted the critics and attacked them for the contradictions in their statements about abstract art. AAA artists had even organized a public protest, picketing the Museum of Modern Art (on April 15, 1940) and distributing pamphlets designed by Ad Reinhardt that queried, “How Modern is the Museum of Modern Art?”

The Museum of Modern Art, founded in 1929, particularly angered the young American abstract artists with its contradictory policy of promoting European abstract movements while at the same time endorsing American social realism and regionalism. Although the Whitney Museum of American Art, which opened in 1931, included a few abstract artists in such shows as the 1936 Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary Painting, the Whitney also focused primarily on American realism 57.

Another New York museum, the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, which was founded a decade later, in 1939, proved to be more supportive of American abstract artists. Later renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, this museum, directed by Hilla Rebay, not only featured the painting of Vasily Kandinsky and the abstract work of European artists but also began to include the work of some Americans. In addition, Rebay provided financial support from the foundation to American artists working in a non-objective style. Esphyr Slobodkina, who had been represented at the museum 58, received a stipend for art supplies in 1940 59.

World War II Changes the Artistic Landscape

The rise of the Nazi Party in Germany in the 1930s, the outbreak of World War II in 1939, and the occupation of Paris in 1940 brought significant changes: approximately 700 artists and 380 architects arrived in the United States between 1933 and 1944 60. Many of these artist-émigrés settled in New York City, creating an international dialogue for American artists. The prestige of the European modernists also focused attention on abstract art and served to validate the work of the American artists who admired them. Josef Albers, László Moholy-Nagy, Fritz Glarner, Hans Richter, Fernand Léger, and Piet Mondrian were refugees who became members of the AAA.

With the help of AAA member Harry Holtzman, Dutch painter Piet Mondrian arrived in New York in October 1940 and joined the AAA three months later. In his Neo-Plastic paintings, Mondrian constructed a dynamic equilibrium using straight lines, rectangular shapes, and primary colors. His growing influence on the work of several group members (even before his arrival in New York) helped to transform the fourth annual exhibition enough that critic Jerome Klein would call the AAA “the national organization of adherents to squares, circles and unchecked flourishes 61.” Klein mentioned Slobodkina in this review, naming her one of the artists to be noted 62.

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Slobodkina organized two parties at her apartment to honor Mondrian: a reception and a tea sponsored by the AAA 63. Although she never adopted a Neo-Plastic vocabulary as did numerous other AAA members 64, her work in the 1940s became increasingly geometric. However, curved edges often defined the irregular geometric forms that dominated Slobodkina’s work during this decade.

Ovals in the Sunset (Sketch) and Monochrome in Gray, both painted in 1942, capture Mondrian’s concept of dynamic equilibrium without repeating his rectangular shapes or adhering to his primary colors. Instead, she challenged his prohibition of arbitrary contours, creating an inventive array of overlapping forms.

Abstract Art Gains Stature in the 1940s

In 1942, the AAA members could boast of an impressive group of abstract artists, including Mondrian, Hélion, Léger, and Moholy-Nagy, who participated in the AAA’s sixth annual exhibition. Although critic Edward Alden Jewell continued to complain about the lack of “striking creative originality” in the work of the Americans, his review did give them credit for “consolidation of more general gains” and mentioned the inclusion of the prominent European artists 65. Jewell’s tone, which was definitely less critical, indicated the growing acceptance of abstract art in the 1940s.

Signaling this change, critic Clement Greenberg wrote a pivotal review of the sixth annual exhibition in The Nation. Greenberg, who, unlike Jewell, enthusiastically supported abstract art and would later become the champion of Abstract Expressionism, praised the work of Esphyr Slobodkina, Hananiah Harari, and Giorgio Cavallon 66. He selected their paintings as the best in the show, emphasizing that “they had in common a fluidity of shape and color that seemed least to violate the character of their medium, in contrast to the ‘geometricians,’ who treat canvas as though it were concrete or plastic 67.”

Greenberg described this AAA show as “the most provocative” of four abstract shows he had seen, but he qualified his praise by adding that this was “not so much because of the merits of the individual contributors as because many of them were comparatively young and so could tell us most about the probable future of abstract art in this country 68.”

Years later, in 1984, Greenberg, who became one of the most important critics of the 20th century, admitted “how arrogant his attitude had been when he reviewed the AAA shows 69.” When he reconsidered his evaluation of the AAA, he confessed that “his eye in the 1930s wasn’t up to the quality of the AAA shows 70.”

Slobodkina’s Work Gains Attention in the 1940s

During the 1940s, Slobodkina developed a mature abstract style and an impressive exhibition record for a young artist. As an active member of the AAA, she continued to exhibit her work in the group’s annual shows and participate in the abstract avant-garde in New York during the war years. She became the group’s assistant treasurer in 1942 and served as its secretary from 1945 until about 1960. (Later, in 1963, she was elected president, and she remained a member throughout her life.)

A. E. Gallatin organized Slobodkina’s first major one-person exhibition at his Museum of Living Art in 1942 71. Although other AAA members had been included in group shows at Gallatin’s museum, hers was one of the few exhibitions that featured the work of a single artist 72. In a review of her exhibition, critic Henry McBride applauded her accomplishments as “a painter of the abstract, who has refinement, good color, and a sense of picture-making among her assets 73.”

In 1940, Gallatin, also a member of the AAA, had won a painting of Slobodkina’s in 1940 at the group’s raffle held to help members Albert Swinden and Balcomb Greene after a fire in their adjacent studios 74. Gallatin had also purchased Composition, 1940, which had been exhibited in a group show at the Museum of Living Art in June–July 1942 75. Composition, 1940, now in the A. E. Gallatin Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is a classic work by Slobodkina with its dynamic hard-edge forms and rich, vibrant colors. When Composition, 1940 was exhibited in the group show, Art News critic Rosamund Frost extolled Slobodkina’s “extremely personal forms and color sense 76.”

While her one-person exhibition was still on view at the Museum of Living Art, Slobodkina’s work could also be seen at another important venue, Peggy Guggenheim’s famous gallery, Art of This Century, which opened in October 1942 and quickly became a meeting place for American and European artists and a center for avant-garde exhibitions. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the director of the Museum of Modern Art, recommended Slobodkina for Peggy Guggenheim’s Exhibition by 31 Women. In a letter dated September 24, 1942, he suggested five “female abstract painters who on the whole seem to me as good as the best of the men in the American Abstract Artists group 77.” Three of the five AAA artists he recommended were chosen to exhibit in the show: Susie Frelinghuysen, I. Rice Pereira, and Esphyr Slobodkina. (Gertrude Greene and Eleanor De Laittre were not included.)

Most of the women in the show were young, and their work was predominantly surrealist. The gallery’s press release declared that “Here then is testimony to the fact that the creative ability of women is by no means restricted to the decorative vein 78.” The reception of the critics to this controversial show was mixed: Edward Alden Jewell wrote that “the exhibition yields one captivating surprise after another 79.”

But when James Stern, art critic for Time magazine, was asked to review the show, he declined, complaining that there were no first-rate female artists and that women should focus on having babies 80. Slobodkina had mixed feelings about the concept of the show: “That was the only time I allowed myself to be in one of those sexist shows because I don’t believe in that. Why women…? As a matter of principle, I always refused to exhibit in shows like ‘Jewish art’ and ‘women painters’ or ‘older artists 81.’”

When Gallatin moved his collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Slobodkina’s painting, Composition, c. 1940, became part of a major museum collection. Installed in a prominent area near the entrance to the museum, an exhibition of the Gallatin Collection opened to the public in May 1943. Edward Alden Jewell pointed out that the art in the collection was being shown all together for the first time, which had not been possible in the smaller exhibition space at New York University 82. He emphasized that “the full impact of the collector’s achievement may now be experienced, and it will be remembered as one of the most significant experiences of the season 83.”

In his review, Jewell listed the many famous European artists in the collection and then the Americans (including Esphyr Slobodkina) who were represented in this prestigious collection. By supporting young American abstract artists and combining their work with the most important European modernists, Gallatin added stature to the Americans and placed them in an important historical context.

Two years later, Gallatin, with the help of curator Henry Clifford, selected paintings for another significant show, Eight by Eight: American Abstract Painting Since 1940, which opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and traveled to the Institute of Modern Art in Boston 84.

This exhibition featured eight paintings by eight American abstract artists—Esphyr Slobodkina, Ilya Bolotowsky, Susie Frelinghuysen, Alice Trumbull Mason, George L. K. Morris, Ad Reinhardt, Charles Shaw, and A. E. Gallatin—and offered a view of their development over a five-year period 85. Slobodkina’s paintings Elegy, 1936–1940 86, and Large Picture, 1943 87, were included in the show.

In Large Picture, Slobodkina repeated the fingerlike forms and dark lines that she used in Composition, c. 1940, but also established the painting’s “dynamic equilibrium” with diagonal shapes that direct the movement back and forth and with overlapping forms that advance and recede in space. The drama of this painting derives from its dynamic composition, its eccentric shapes, and its opulent color.

Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth

This work was formerly entitled Large Picture.

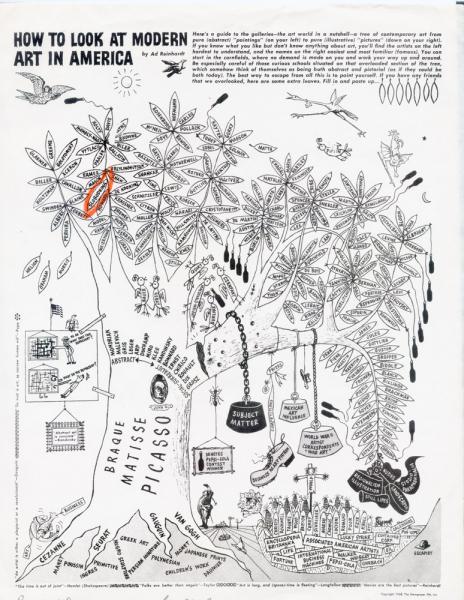

By 1946, Slobodkina had become well-known among abstract artists and New York art critics. When Ad Reinhardt (who had also shown his paintings in the Eight by Eight exhibition) created his cartoon tree diagramming the branches of abstract art and its break from realistic art, he created a leaf that prominently bore Slobodkina’s name.

Titled How to Look at Modern Art in America (fig. 14), Reinhardt’s vision of modern art placed Slobodkina’s leaf on the branch growing from the roots of Post-Impressionism through Cubism to the most abstract side of the tree and then branching off from Mondrian, Malevich, and Gris 88.

When Slobodkina was featured in a one-person show at Norlyst Gallery in 1947, Edward Alden Jewell remarked that her “work in the non-objective field is extremely well known 89.” Her exhibition at Norlyst Gallery consisted of 31 paintings, 2 collages, and 5 pieces of sculpture 90.

In another review of the show, Art Digest critic Josephine Gibbs described Slobodkina’s paintings as “cool, thoughtful, non-objective paintings 91.” Gibbs observed that in the realm of abstract art “women more than hold their own with the men” and that “one of the best of them” was Esphyr Slobodkina 92. Gibbs voiced admiration for the artist’s success: “That such a large exhibition in such a circumscribed métier should be exciting, stimulating and varied rather than a trifle monotonous is sufficient testimony to the artist’s technical skill and ability to infuse these expert compositional patterns with communicated mood as well 93.”

A New Avant-Garde

Despite the energy generated by the participation of European abstract artists during the war years, the AAA lost some of its vitality. Ironically, as the climate for abstract art improved and opportunities for abstract artists multiplied, the significance of the AAA declined. It had served its purpose. Attendance figures for the sixth and seventh annual exhibitions (March 1942 and March–April 1943) reflected the fading impact of the group and the competition from new galleries exhibiting contemporary abstract art. Alice Trumbull Mason’s letter to the membership on May 23, 1944, noted: “It has become apparent that, as public interest in abstract art has increased, the members have shown less and less interest in furthering the aims for which the group was founded 94.”

Gradually, many of the group’s artists became less involved or dropped out, so that in the spring of 1947 only 14 of the original 39 founding members participated in the eleventh annual exhibition at the Riverside Museum 95. Neither the exhibitions, nor the group itself, functioned any longer as an avant-garde force in New York City 96. Paradoxically, the stature the AAA attained with its international membership may have reinforced the perception that the group was not “American” enough to represent the United States after World War II.

The emergence of the Eighth Street Artists’ Club (The Club) after the war rallied a larger group of artists and supplanted the AAA as a forum for abstract art. In spite of this, the remaining AAA members, including Slobodkina, continued to exhibit as a group. Philip Pavia, one of the founders of The Club, recalled the early meetings that led to its official formation in 1949: “Right after the war came the big change. . . . 1946 was the big year. It was quite noticeable, our little table at the Waldorf Cafeteria started to get bigger and bigger. . . . The whole breadth of avant gardism really started after the war when the refugees went home and we were on our own. We opened our club 97.”

Other changes defined this new avant-garde: American artist Jackson Pollock painted Cathedral in 1947, dripping linear skeins of enamel and aluminum paint on his canvas, weaving a continuous pattern. Created spontaneously without any sketches, Pollock’s paintings from this period marked a new kind of abstract art, Abstract Expressionism, and critic Clement Greenberg designated Pollock “the most powerful painter in contemporary America and the only one who promises to be a major one 98.”

Slobodkina Rejects Abstract Expressionism

Mocking Abstract Expressionism as the “drip, splash, and smudge school 99,” Esphyr Slobodkina rejected this new process of painting. Her approach to painting was not spontaneous; she resolutely continued to use flat, clearly defined geometric shapes and preconceived compositions made from enlarging preparatory drawings 100.

First, she made small sketches and even traced photographs or diagrams of machinery, which she would then work on by overlaying them with other sketches, turning them in a different direction, or simplifying their compositions 101. After she had completed a small drawing, she divided it into squares and enlarged it by drawing it onto a larger piece of paper with the same number of squares 102. When she finished this process, she darkened the lines on the back of the sketch with a soft pencil and transferred it to a board prepared with gesso by drawing over the lines on the front, depositing the graphite on the new surface 103.

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Slobodkina’s carefully orchestrated compositions and her laborious working procedure contradicted the tenets of Abstract Expressionism. In addition, her selection of work for her next one-person exhibition, Tangents at the Norlyst Gallery in 1948, challenged the boundaries of “fine art” with examples from the wide range of her creative projects. She included textiles, dolls, children’s book illustrations, collages, and constructions, along with a group of still life paintings 104.

With this unconventional assortment of work, the 1948 Norlyst show marked a transition period for Slobodkina. By the autumn of 1948, she had also declared her independence from the New York art center, relocating her studio to Great Neck, New York, where she had designed and built a new house and a studio.

Not part of the postwar group of artists called the New York School 105, Slobodkina did not participate in the activities and exhibitions of this new avant-garde: The Club; the landmark exhibition 9th St.: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, in 1951; or the Stable Gallery annual exhibitions from 1953 to 1957 106. Instead, sequestered in her Great Neck studio in 1950, she painted Levitator #1 and Turboprop Skyshark, two works that extended her artistic reach with their direct references to specific mechanical subjects.

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Discussing this work, Slobodkina noted that it is “constructed just like an airplane. There’s a body, there’s a wing structure…I don’t believe in this Kandinsky floating stuff. I’m not a ghost…I’m still building structures…I’m very architectonic.”

Geometric and abstract, but clearly an airplane, the central image in Turboprop Skyshark fills her painting to its edges with bold, diagonal movements. The diagonal wings and propellers imply movement, and the overlapping shapes define a shallow but almost three-dimensional space. Slobodkina created the potential for flight with stark contrasts of color, which imply movement: the white and blue areas appear to advance toward the viewer, and the black and brown shapes recede into space.

Undoubtedly, designing her house and studio in Great Neck focused her attention on architecture, mechanics, and engineering, and, perhaps, her strident rejection of Abstract Expressionism motivated her to reexamine the possibilities for abstract art. When Slobodkina exhibited Turboprop Skyshark in a one-person show at the New School in 1951, a review in The Art Digest noted her increased emphasis on dynamism: “Although concise and flatly painted, the abstractions of Esphyr Slobodkina have a drama that arises from subtle use of opaque color and an intricacy of spatial effects. This drama—much of it that of the mechanical in the modern world—is evident in Turbo-Prop Sky Shark sic where dynamic tensions are created by an overlapping and interweaving of inventive shapes 107.”

Another review, by Stuart Preston in the New York Times, applauded her as “one of the more convincing and assured abstract painters of today 108.” He also emphasized the dynamic quality of her paintings:

She sets her geometrical shapes flying all over the picture surface, conveying, in their movement and in the clean-cut impact of their inter-penetrations, the dynamism that gives these designs such admirable tension. These knife-edged shapes have no body; their pure color is not altered by any transitoriness of natural light; yet, they are not flat. They advance and recede because of her ingenious play with perspective along the contours . . . 109

Although Slobodkina denounced the process of the Abstract Expressionists, the dynamic quality of her own compositions—once flatter and more tightly held in equilibrium—may have been her response to their emphasis on action painting 110.

The Whitney Annual Exhibitions

Absent from the most avant-garde exhibitions in the 1950s, Slobodkina, nonetheless, was represented in prominent venues and continued to receive recognition from critics. Reversing its “reception” of American abstract art in the 1930s, the Whitney Museum of American Art proved to be one of the most important and inclusive venues for abstract artists during the 1950s. A broad range of artists, from those who worked in a conservative tradition to those in the vanguard, was invited by the museum curators to participate in its Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting. In the catalog for the 1950 annual exhibition, museum director Hermon More wrote that “the present exhibition includes many styles and tendencies, but like its predecessors, chief emphasis has been placed on what seems to be the predominant trends in contemporary painting. If modern art in its many forms, such as expressionism, abstraction, and surrealism, predominates in the show, it is because it is the leading movement in art today, and has influenced the greatest number of younger artists 111.”

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Purchase, 53.6

Esphyr Slobodkina’s work was chosen for the Whitney Annual in 1950 and for annuals throughout the decade 112. In 1952, her painting Composition with White Ovals, 1952 113, was exhibited in the Whitney Annual and then purchased by the museum for its permanent collection. In a review of the work of approximately 155 artists in this Whitney Annual, critic Ralph M. Pearson selected Slobodkina’s painting as one of 16 that deserved the accolade of “top-level distinction 114.”

Continuing to present an inclusive survey of contemporary American painting, the 1953 Whitney Annual again provided an opportunity for Slobodkina to exhibit her work in a prestigious museum. New York Times reviewer Howard Devree noted that “as usual, the annual of contemporary American painting at the Whitney Museum covers all phases of work being done today, from ultra-realism to violent expressionism and complete abstraction 115.” Certainly, his description “violent expressionism” indicated Abstract Expressionism, and his category “complete abstraction” described Slobodkina’s work. Devree also placed Slobodkina’s entry, her “suggestive abstract ‘Flight,’” among the paintings he considered the “outstanding work” in the show 116.

Slobodkina’s Exhibition at the John Heller Gallery

The following year, Slobodkina exhibited this same painting, Flight, c. 1953, in a one-person show at the John Heller Gallery in New York City. She also exhibited Composition in an Oval, 1953, one of her most masterful paintings.

Grey Art Gallery, New York University

Commanding attention with its large, oval shape (32½” x 61½”), this painting presents a dynamic aggregation of some of her most important motifs: the central fingerlike forms used in Composition, c. 1940, in the Gallatin Collection; the keyhole shapes (one in the center and one on the far right) similar to Abstraction with Black Shape, c. 1945—1951, exhibited in the Whitney Museum Annual in 1951; and the mechanical hinges recalling her interest in architectural forms. Yet, the most dramatic part of the painting is the large white ladder on the right. This image harkens back to Miró’s famous painting Dog Barking at the Moon, 1926, which Slobodkina would have seen in the Gallatin Collection. Miró, however, used a ladder to draw the viewer into a surreal landscape; Slobodkina positioned her ladder leaning outward toward the viewer, seeming to provide an escape route.

The Art Digest critic Margaret Breuning described Slobodkina’s work at the Heller Gallery: “each painting might be considered a ‘self-contained’ cosmos” and she pointed to Composition in an Oval as “an outstanding canvas 117.” However, she also compared the paintings to “early cubist flat-patterning 118,” which placed Slobodkina’s work in the context of an earlier avant-garde. Emily Genauer, reviewing the show in the New York Herald Tribune, concluded that Slobodkina “might be called a classic among abstractionist painters 119.” Genauer continued:

Working in this vein for many years, she paints canvases that are as neatly put together of geometrical shapes as a kaleidoscopic image. Her color is clear and pure, her compositions are three-dimensional. Color areas hold together as firmly as if each had a magnetic attraction for the others. This is most attractive and skilled painting 120.

Genauer’s description, too, praises Slobodkina but also associates her work with an earlier abstract style.

Pop Art, Hard-Edge Painting, and Minimal Art

That Slobodkina would not exhibit in a major one-person show in New York City again until 1980 is at once a measure of the changing nature of the avant-garde as well as her own personal and artistic life. With her commitment to geometric abstract art, she continued to participate in the AAA exhibitions. But, like other geometric artists, she found herself with fewer opportunities as Abstract Expressionism proliferated during the 1950s. Then, all abstract art was challenged by Pop Art, which focused on figurative imagery from popular culture.

Like Pop Art, hard-edge painting—another reaction to Abstract Expressionism—became widespread in the 1960s. By avoiding Cubist and Neo-Plastic compositional strategies and incorporating the large formats and nonrelational surfaces of Abstract Expressionism, the geometric abstract art of the 1960s and 1970s presented an original direction in American art. However, despite the fact that hard-edge painting was influenced by some aspects of Abstract Expressionism, it occurred as a reaction to that “painterly” movement.

A Continuing Tradition of Geometric Abstract Art

Hard-edge painting can be placed within a continuing tradition of geometric abstract art in the United States, which includes the work produced in the 1930s and 1940s. The fear of associations with the “old” instead of the “new”—indicating a lack of progress—prompted some critics and artists in the 1960s to avoid the connections between these two periods that focused on geometric forms.

However, the geometric art of the 1930s and 1940s created by the members of the AAA should be connected to the hard-edge painting of the 1960s and 1970s. The consolidation of the geometric abstract tradition, from all decades of the 20th century, creates a more accurate and a more complex context through which to view the development of abstract art in the U.S. It also establishes the important role of AAA members like Slobodkina, Bolotowsky, and Reinhardt as critical links between the two periods 121.

Although Slobodkina’s work in the 1960s could be considered geometric abstraction—it is defined by clear, hard edges painted between geometric shapes—it remained closer to Cubism with its overlapping planes of color. She may have been influenced to some extent by the size and scale of hard-edge painting and Minimal Art, but she continued to work independently, outside the parameters of these movements.

Her captivating painting Triptych in Old Rose, 1964, combines three panels to create a larger painting, but the overlapping forms and eccentric shapes do not suggest the simplified and often much larger, hard-edge paintings of Kenneth Noland, Ellsworth Kelly, and Frank Stella.

Hillwood Art Museum, Long Island University.

Slobodkina’s Monochrome in Beige, 1968, repeated the triangular white sail-like forms of the Triptych in Old Rose, but the “sails” are muted with beige and gray and appear less sail-like and more abstract. In this painting, Slobodkina approached the monochromatic quality of Minimal Art, but she continued to insist on a composition with a dynamic array of overlapping shapes, viewing Minimal Art paintings as merely “empty spaces 122.”

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

Changes in Slobodkina’s Life in the 1960s and 1970s

During the 1960s and 1970s, Slobodkina’s life changed significantly. In 1960, after a long friendship, she married William Urquhart, a businessman she had met at the sixth AAA annual exhibition in 1942. Another change came in 1963, when her husband died. That same year, she was elected president of the AAA and served in this office until 1966, when she assumed the chairmanship of the Publications Committee. As chair, she was responsible for the group’s publication American Abstract Artists 1936–1966 123.

In 1978, Slobodkina moved to Hallandale, Florida, with her mother and her sister Tamara. She had a one-person show in Florida at the Hollywood Art Museum the next year. Then, in 1984, the Art and Culture Center of Hollywood, Florida, organized a large retrospective exhibition of her work, Esphyr Slobodkina: An Introspective. Slobodkina preferred the title “An Introspective” to “A Retrospective,” rejecting the concept of a chronological study of her work.

In fact, she wrote in her catalog essay for the show: “Frankly, I never gave a damn what people thought. As a result of that I always painted, sculpted, constructed, made collages, wall hangings, ‘Serendipographs,’ ‘Glass Sandwiches,’ dolls, books, clothes, furniture, etc., etc. and all at the same or approximately the same time 124.”

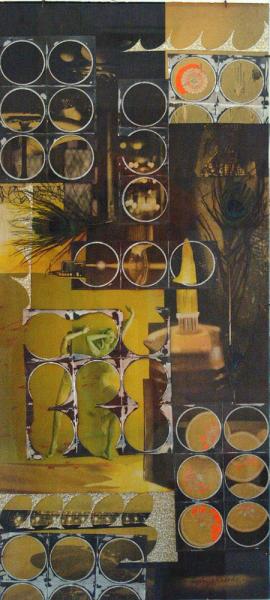

Collection of Micki and Dohn Samuel Schildkraut

Slobodkina trademarked “Serendipograph” in 1961 to describe her collages that resulted from fortuitous happenstance.

Collection of Micki and Dohn Samuel Schildkraut

Not until the Feminist Movement pushed the boundaries of “fine art” outward to encompass crafts and other decorative arts was Slobodkina’s inclusive artistic strategy considered more acceptable within the dialogue of mainstream art 125.

Her lack of interest in current trends and concepts of “progress,” or “development,” made her ask, “And why do I have such a hard time dividing my work into definite periods? 126” Although she certainly developed a recognizable style, Slobodkina’s work does not always follow a linear progression. She worked intuitively: “I don’t feel a traitor to my chosen art if, in the middle of preparations for an exhibition of abstract paintings, catching sight of an exceptionally attractive bouquet of flowers, I have a strong urge to paint it, I simply go ahead, and paint it 127.”

Rediscovered as a Pioneer of American Abstract Art

New attention was focused on Slobodkina’s work in the 1980s, when she was rediscovered as a pioneer of American abstract art. In 1980, her paintings from the 1930s and 1940s were featured in New York City in an exhibition at the Sid Deutsch Gallery. With additional shows at the Sid Deutsch Gallery in 1982, 1985, and 1988, her work again became well-known among curators and collectors 128.

In 1983, two of Slobodkina’s works, Construction No. 3, 1935, and Ancient Sea Song, 1943, were exhibited in Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927—1944 at the Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, in Pittsburgh and traveled to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City in 1984 129. This landmark exhibition presented the first comprehensive study of abstract art in the United States from 1927, when Gallatin established the Gallery of Living Art, until 1944, the year of Mondrian’s death 130. In this exhibition, curators John R. Lane and Susan C. Larsen brought the early work of Esphyr Slobodkina and many of her abstract artist-colleagues to public attention in a major New York museum.

During the 1980s and the 1990s, Slobodkina’s work gained attention when pieces were acquired by important collectors and exhibited in major museums 131. The Ebsworth Collection: American Modernism, 1911–1947, organized by the Saint Louis Art Museum in 1987, and The Patricia and Phillip Frost Collection: American Abstraction 1930–1945, organized by the National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C., in 1990, both served to document Slobodkina’s contribution and place her in a significant historical context.

In 1992, a retrospective exhibition of Slobodkina’s painting and sculpture, as well as examples of her children’s book illustrations and fabric design, opened at the Tisch Gallery, Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts, and traveled to the Sidney Mishkin Gallery at Baruch College, in New York City. A catalog was published with essays by curators Gail Stavitsky and Elizabeth Wylie 132. Holland Cotter, in a New York Times review titled “Wolfing Down Modernism Whole,” emphasized the importance of the abstract avant-garde in the 1930s and explained that these artists, including Slobodkina, who worked between the two World Wars were “trying to digest three decades of imported styles in a hectic few years 133.”

In another review of this show, Art in America critic Janet Koplos perceptively discussed two issues still raised by Slobodkina’s work: “The exhibition and catalogue provoked me to think about when and why an artist’s use of a variety of mediums becomes a liability, and about how dangerously easy it is to remember art movements by the work of a few major practitioners rather than as the messy assortment of activities they actually were 134.”

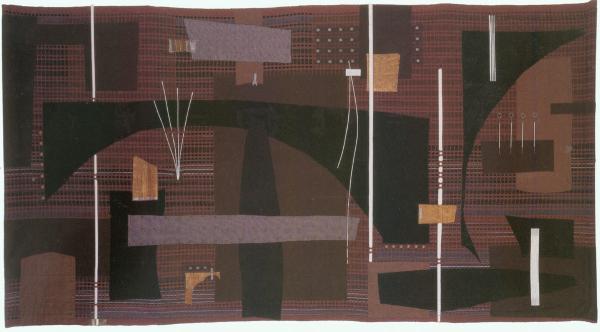

Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation

This cloth wall-hanging was exhibited at “Diversity” and a year later was installed in the official residence of the United States Consul General to Hong Kong as part of the U.S. Department of State’s “ART in Embassies Program,” 2003.

A decade later, in March 2002 (a few months before her death), the issue of the variety of Slobodkina’s creative work—and her refusal to hide her work with textiles and other so-called decorative arts—was directly addressed in an exhibition aptly titled Diversity at the Kraushaar Galleries in New York City. Grace Glueck, New York Times art critic, observed that Slobodkina’s “paintings and collages of interlocking geometric forms are considered her signature works 135.” Then she acknowledged and praised Slobodkina for the remarkable versatility of her work: “None of Ms. Slobodkina’s works suffer from her versatility. They are all of a creative piece, and a pleasure to behold 136.” Finally, in the 21st century, the perceptions of curators and critics regarding the status of “fine arts” and “decorative arts” had caught up with Slobodkina’s.

A concurrent exhibition, Modernism and Abstraction: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, at the National Academy of Design Museum in New York City, brought to attention a group of less well-known artists who represented American modernism. Grace Glueck also reviewed this show, which included Crossroad #2, c. 1942—45, by Slobodkina, and described the exhibition as “an illuminating glimpse of what went on in American art across a 75-year period 137.”

Glueck recognized the importance of these less well-known artists: “Happily revived here, too, are a handful of American Modernists of the 1930’s and 40’s, among them Jan Matulka, Theodore Roszak, Esphyr Slobodkina, Suzy Frelinghuysen, Carl Holty, Ilya Bolotowsky, George L.K. Morris, Gertrude Greene and Albert Gallatin 138.” As part of the avant-garde before World War II, Esphyr Slobodkina, along with her colleagues in the American Abstract Artists group, were applauded for their role in the development of American art.

Spanning most of the 20th century, the narrative of Esphyr Slobodkina’s remarkable life—her independence, her varied talents, her unfailing commitment to abstract art—helps to create a broader perspective through which to view the development of abstract art in the United States.

Copyright © 2008 Sandra Kraskin

About the Author

Under Dr. Kraskin’s direction since 1989, the Mishkin Gallery has become well-known as a venue for small museum-quality exhibitions that highlight innovative scholarship, significant artists, and multicultural concerns. She has organized exhibitions that have challenged and revised the history of American modernism. Her publications that might be labeled “Revisionist” include the following exhibition catalogs: The Indian Space Painters: Native American Sources for American Abstract Art, 1991 (with essays by Ann Gibson, Barbara Hollister and Allen Wardwell); Pioneers of Abstract Art: American Abstract Artists, 1936-1996, 1996; Reclaiming Artists of the New York School: Toward a More Inclusive View of the 1950s, 1994; and Wrestling With History: A Celebration of African American Self-Taught Artists, 1996.

Dr. Kraskin received her Ph.D. in American Art from the University of Minnesota in 1993 and did graduate work at Harvard University and New York University’s Institute of Fine Art. She taught at North Hennepin Community College in Minneapolis from 1969 to 1986 and, from 1972 to 1974, also directed the Summer Art Program at Southampton College of Long Island University in Southampton, New York.

Dr. Kraskin is the author of Life Colors Art: Fifty Years of Painting by Peter Busa, 1992, and Howard Daum: Indian Space Painter, 2004. She curated the traveling exhibition of the work of Esphyr Slobodkina and the author of this major essay from Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction, 2009, Hudson Hills Press.

Endnotes

1Esphyr Slobodkina, “IBM Exhibition Article: A Small Abstract Drawing” in Notes for a Biographer, vol. 3-b (Hallandale, Fla.: privately printed, 1983), 5.

2The exhibition also traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

3Her work was acquired by the following major collectors: Barney A. Ebsworth, Patricia and Phillip Frost, Penny and Elton Yasuna, and Dr. Peter B. Fischer. In the late 1980s and the 1990s, her work was included in exhibitions at the following museums: the Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, Missouri; the National Museum of American Art of the Smithsonian Museum, Washington, D.C.; the Worcester Museum of Art, Worcester, Massachusetts; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York; and Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, California.

4In 1992 a major traveling retrospective organized by Gail Stavitsky and Elizabeth Wylie opened at Tufts University Art Gallery, Medford, Massachusetts, and traveled to the Sidney Mishkin Gallery at Baruch College, The City University of New York. This 2008 exhibition and its catalog reassess her work and include a discussion of the recognition she received in the decade between the 1992 exhibition and her death in 2002.

5Gail Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” in Gail Stavitsky and Elizabeth Wylie, The Life and Art of Esphyr Slobodkina (Medford, Mass.: Tufts University Art Gallery, 1992), 5.

6Ibid., 8.

7Esphyr Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2 (Great Neck, N.Y.: privately printed, 1980), 293.

8Ibid.

9Ibid., 310.

10Archives of American Art, “Adventures with Bolotowsky,” Archives of American Art Journal 22(1): 16.

11Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 320.

12Ibid.

13Ibid.

14Ibid., 321.

15Ibid. This painting was probably Still Life with Bananas, c. 1932.

16Ibid., 325.

17Ibid.

18Ibid.

19Ibid., 332.

20Ibid., 333. This painting was probably Komar Farm, 1933, Collection of the Heckscher Museum of Art.

21Ibid., 336.

22Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” in Art and Sexual Politics, ed. Thomas B. Hess and Elizabeth C. Baker (New York: Collier-Macmillan, 1974), 30.

23Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 349.

24Ibid.

25Ibid.

26Two letters from Bolotowsky to Mrs. Ames document that Bolotowsky and Slobodkina were at Yaddo from August 30, 1934, to about December 25, 1934. Ilya Bolotowsky, “Letter to Mrs. Ames,” August 24, 1934, Yaddo Records (1870–1980), Box 230, New York Public Library; Bolotowsky, “Letter to Mrs. Ames,” December 20, 1934, Yaddo Records, Box 230, New York Public Library.

27Ilya Bolotowsky, interview with Sandra Kraskin, New York City, August 1978.

28Esphyr Slobodkina, Flowers in the Sink, 1934, Oil on canvas, 22″ x 17½”, Collection of the Slobodkina Foundation.

29Louise Averill Svendsen and Mimi Poser, “Interview with Ilya Bolotowsky,” in Ilya Bolotowsky (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1974), 16. Bolotowsky discussed seeing Mondrian’s work at the Gallery of Living Art in 1933.

30Susan C. Larsen, “The Quest for an American Abstract Tradition, 1927—1944,” in Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927–1944, ed. John R. Lane and Susan C. Larsen (Pittsburgh: Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute; New York: Abrams, 1983), 18.

31Ibid. The Museum of Modern Art did not open until 1929, two years after Gallatin’s Gallery of Living Art, and did not present its landmark show Cubism and Abstract Art until 1936.

32Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 416.

33A. E. Gallatin, introductory essay, “The Plan of the Museum of Living Art,” in A. E. Gallatin Collection: “Museum of Living Art” (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1954), 5.

34Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 369. Slobodkina worked in a textile printing company in Clifton, New Jersey, after she returned from Yaddo at Christmas in 1934.

35Ibid., 416.

36Ibid.

37Ibid., 376. Bolotowsky’s abstract painting Abstraction, exhibited in the first AAA show, was dated 1934. See photo in Archives of American Art, “Adventures with Bolotowsky,” 17.

38The exact dates of Slobodkina’s WPA/FAP employment are unknown. See footnote 58 in Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 35. Stavitsky states that researchers at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, could only locate an employment card dated April 25, 1938, probably referring to her termination.

39Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2. Plate VII is a reproduction of her membership card dated 1934.

40Exhibited in a government-sponsored public art exhibition, this painting supports the movement to free the Communist activist Angelo Herndon, which was supported by the Artists’ Union. Cited in Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 15.

41Emily Genauer, “Public Art Exhibition Quality Varied,” New York World-Telegram, 25 Jul. 1936: 14B.

42Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 395.

43Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 19.

44Ibid.

45Ibid.

46Susan Carol Larsen, The American Abstract Artists Group: A History and Evaluation of Its Impact Upon American Art (Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms, 1975), 222–23.

47Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne, “The American Abstract Artists and the WPA Federal Art Project,” in The New Deal Art Projects: An Anthology of Memoirs, ed. Francis V. O’Connor (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972), 228.

48Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 427. The Pot-Bellied Stove is now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

49Ibid., 426.

50Ibid., 427.

51Sandra Kraskin, “American Abstract Artists: Pioneers of Abstract Art,” in Pioneers of Abstract Art: American Abstract Artists, 1936–1996 (New York: Sidney Mishkin Gallery, Baruch College, 1996), 5.

52Ibid., 8.

53Edward Alden Jewell, “Abstract Artists Open Show Today,” New York Times, 6 Apr. 1937, 21:5.

54Jerome Klein, “Abstract Artists Make New Stand,” New York Post, 10 Apr. 1937. From Ilya Bolotowsky Estate Files. Cited in Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 17.

55Jerome Klein, “Plenty of Duds Found in Abstract Art Show: More Fizzles Than Explosions in Display at Fine Arts Building,” New York Post, 19 Feb. 1938, 18.

56Edward Alden Jewell, “Abstract Artists Show Their Work,” New York Times, 8 Mar. 1939, 17:4.

57Larsen, The American Abstract Artists Group, 44-45.

58Howard Devree, “A Reviewer’s Notebook,” New York Times, 13 Dec. 1942, X9.

59Joan M. Lukach, Hilla Rebay: In Search of the Spirit in Art (New York: George Braziller, 1983), 152.

60Cynthia Jaffee McCabe, “A Century of Artist-Immigrants,” in The Golden Door: Artist-Immigrants of America, 1876–1976 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976), 31.

61Jerome Klein, “American Abstract Artists in Annual Show,” New York Post, 8 Jun. 1940. Slobodkina Foundation Files.

62Ibid.

63Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 616—17.

64Ilya Bolotowsky, Harry Holtzman, Burgoyne Diller, Charmion Von Wiegand, Fritz Glarner, Alice Mason, Albert Swinden, Charles Shaw, and Jean Xceron were AAA members who worked in the Neo-Plastic style.

65Edward Alden Jewell, “Abstract Artists Hold Sixth Show,” New York Times, 10 Mar. 1942, 24.

66Clement Greenberg, “Review of Four Exhibitions of Abstract Art,” The Nation (May 2, 1942), reprinted in Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. I: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944, ed. John O’Brian (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 104.

67Ibid.

68Ibid., 103.

69Clement Greenberg, “Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927—1944.” Presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art symposium on the occasion of the exhibition Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927—1944 (curators John H. Lane and Susan C. Larsen), 8 Sept. 1984.

70Ibid.

71Although she had exhibited in a one-person show at the New School for Social Research in November 1938, this show at the Museum of Living Art was an important museum exhibition.

72Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 24.

73Henry McBride, “Attractions in the Galleries,” New York Sun, 11 Dec. 1942, 32.

74Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 610-11. This painting, Composition, c. 1939, is in the Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

75Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 23.

76R[osamund]F[rost], “Abstract,” Art News 41:39. Cited in Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 23.

77Jasper Sharp, “Serving the Future: The Exhibitions at Art of This Century 1942—1947” in Peggy Guggenheim & Frederick Kiesler: The Story of Art of This Century, ed. Susan Davidson and Philip Rylands (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2004), 291—92.

78Ibid, 292.

79Edward Alden Jewell, “31 Women Artists Show Their Work,” New York Times, 6 Jan. 1943. Cited in Sharp, “Serving the Future,” 292.

80Sharp, 292.

81Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 24.

82Edward Alden Jewell, “A.E. Gallatin’s Art in a New Setting,” New York Times, 15 May 1943, 16.

83Ibid.

84Eight by Eight: American Abstract Painting Since 1940 was partially reconstructed at the Washburn Gallery, 820 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, Oct. 1—25, 1975. A pamphlet was produced to document the show.

85Washburn Gallery, Eight by Eight: American Abstract Painting Since 1940, Oct. 1—25, 1975, unpaginated pamphlet. Susie Frelinghuysen’s first name was also spelled Suzy.

86Elegy may be the same painting that was later titled Irish Elegy. The measurements of the two paintings correspond. Stavitsky dates Irish Elegy circa 1938 and cites the measurements as 32″ x 17¼” (see checklist of Gail Stavitsky and Elizabeth Wylie, The Life and Art of Esphyr Slobodkina, number 16, page 74). The Washburn pamphlet, Eight by Eight: American Abstract Painting Since 1940, dates Elegy 1936-40 and cites the measurement as 32″ x 17″.

87Large Picture was later titled Ancient Sea Song and listed with the new title in the 1946 AAA yearbook on page 59. See Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 26.

88Ad Reinhardt, How to Look at Modern Art in America, The Newspaper PM, Inc., 2 June 1946, Slobodkina Foundation Archives. Cited in Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 26.

89Edward Alden Jewell, “Blakelock Honored,” New York Times, 27 Apr. 1947, X10.

90J[osephine]G[ibbs], “Fifty-Seventh Street in Review,” Art Digest (May 1, 1947):20.

91Ibid.

92Ibid.

93Ibid.

94Archives of American Art, “American Abstract Artists Society,” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and New York, Microfilm Roll NY 59-11. Cited in Larsen, The American Abstract Artists Group, 393.

95Larsen, The American Abstract Artists Group, 398.

96However, the American Abstract Artists group is still an active organization. Its members exhibit as a group and continue to be advocates of abstract art.

97Archives of American Art, “The Artist Speaks: Part Six,” Art in America 53 (August—September 1965):111.

98Clement Greenberg, “The Present Prospects of American Painting and Sculpture,” Horizon (October 1947). Cited in Francis V. O’Connor, Jackson Pollock (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1967), 41.

99Slobodkina, “IBM Exhibition Article,” Notes for a Biographer, vol. 3-b, 5.

100Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2, 472-473.

101Ibid.

102Ibid, 473.

103Ibid, 474.

104J[osephine]G[ibbs], “Fifty-Seventh Street in Review, Tangents,” Art Digest (May 15, 1948):19.

105The term “New York School” is often used in a broader sense than “Abstract Expressionism.” The New York School refers to avant-garde artists who worked in New York City in the 1940s and 1950s.

106Some members of the AAA did participate in the New York School exhibitions. For example, six of the AAA members who exhibited with the group at the American-British Art Center from March 12 to April 1, 1951, were also listed on the poster for 9th St.: Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, which opened two months later on May 21, 1951. They were Lewin Alcopley, Giorgio Cavallon, Perle Fine, Richard Lippold, George McNeil, and A.D.F. Reinhardt.

107M[ary]C[ole], “Esphyr Slobodkina,” Art Digest (March 15, 1951):27.

108Stuart Preston, “Chiefly Modern,” New York Times, 25 Mar. 1951, 9.

109Ibid.

110See Harold Rosenberg, “The American Action Painters,” Art News 51 (Dec. 1952), 22—23, 48—50.

111Hermon More, “Introduction,” 1950 Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting, Nov. 10—Dec. 31, 1950, unpaginated exhibition brochure (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art).

112Slobodkina’s work was included in Whitney Annuals in 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1958. Cited in Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 39, footnote 135.

113Ovals in the Sunset (Sketch), 1942, Oil on gessoed masonite, 11.01″ x 7.04″, Collection of the Heckscher Museum, appears to be the sketch for Composition with White Ovals, 1952, Oil on gessoed panel, 34½” x 20¾”, Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. The larger painting is dated a decade later.

114Ralph M. Pearson, “A Modern View: The Whitney Annual,” Art Digest (Dec. 15, 1952):28.

115Howard Devree, “Round-Up and Solo: The Whitney Opens Its Painting Annual—One-Man Shows and a Group,” New York Times, 18 Oct. 1953, X9.

116Ibid.

117M[argaret]B[reuning], “Reviews: Esphyr Slobodkina,” Art Digest (Feb. 1, 1954):20.

118Ibid.

119E[mily]G[enauer], “Current Gallery Exhibits: ‘Classic’ Abstractions,” New York Herald Tribune, 28 Feb. 1954, 9.

120Ibid.

121For more information, see Kraskin, “American Abstract Artists,” 25.

122Esphyr Slobodkina, “Introspective Thoughts,” in Esphyr Slobodkina: An Introspective (Hollywood, Fla.: Art and Culture Center of Hollywood, 1984), unpaginated.

123American Abstract Artists, American Abstract Artists 1936-1966 (New York: Ram Press, 1966). With Introduction by Ruth Gurin.

124Slobodkina, “Introspective Thoughts,” unpaginated.

125During the 1970s, for example, feminist artist Judy Chicago created The Dinner Party, 1974—79. This work, now at the Brooklyn Museum, is constructed from mixed media, including porcelain and textiles.

126Slobodkina, “Introspective Thoughts,” unpaginated.

127Ibid. Slobodkina’s exhibition Tangents at the Norlyst Gallery in 1948 is an example. She included still life paintings, although she was an abstract painter.

128Stavitsky, “The Artful Life of Esphyr Slobodkina,” 31.

129The exhibition also traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

130John R. Lane, “Foreword,” in Lane and Larsen, eds., Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, 1927–1944, 7.

131See footnote #3.

132Stavitsky and Wylie, The Life and Art of Esphyr Slobodkina.

133Holland Cotter, “Review/Art: Wolfing Down Modernism Whole,” New York Times, 11 Dec. 1992, C29.

134Janet Koplos, “Esphyr Slobodkina at Mishkin Gallery, Baruch College,” Art in America (May 1993):123.

135Grace Glueck, “Esphyr Slobodkina ‘Diversity,’” New York Times, 8 Mar. 2002. Slobodkina Foundation Files.

136Ibid.

137Grace Glueck, “From the Smithsonian, A Modern Tasting Menu,” New York Times, 8 Feb. 2002. Slobodkina Foundation Files.

138Ibid.

139This 2008 exhibition and its catalog reassess Esphyr Slobodkina’s contribution as a pioneer of abstract art and include a discussion of the acclaim she received in the last decade of her life, from her 1992 retrospective at the Tufts University Art Gallery to her death in 2002.