by Ann Marie Mulhearn Sayer, President, Slobodkina Foundation

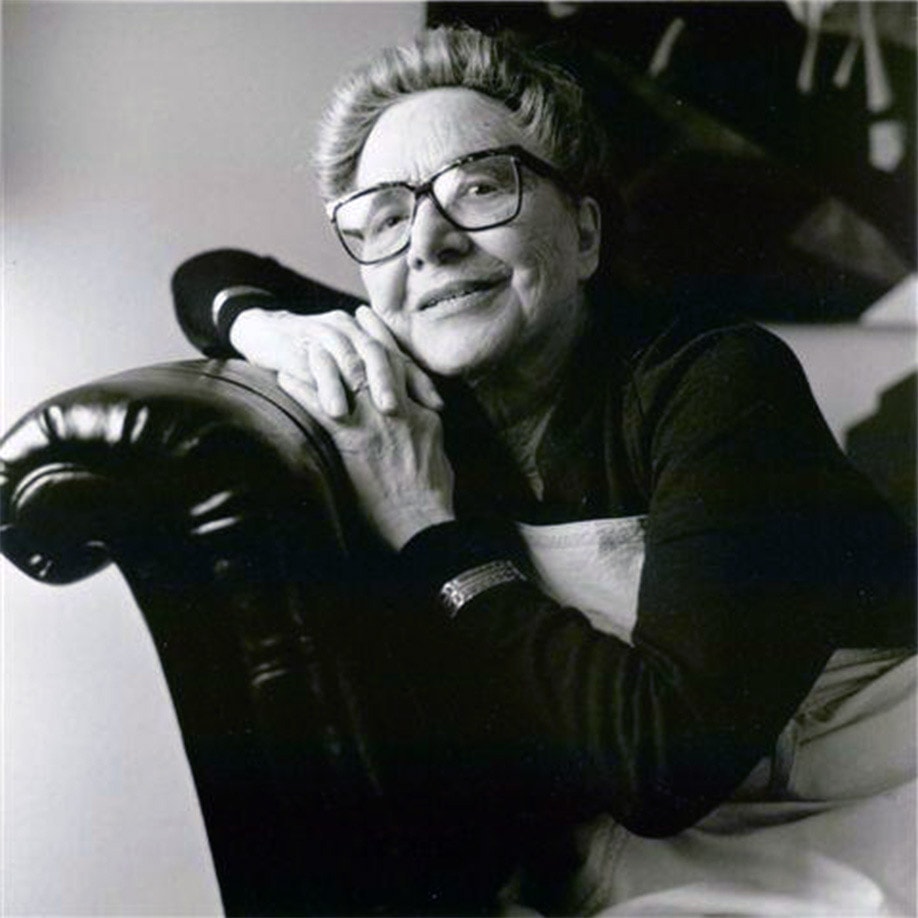

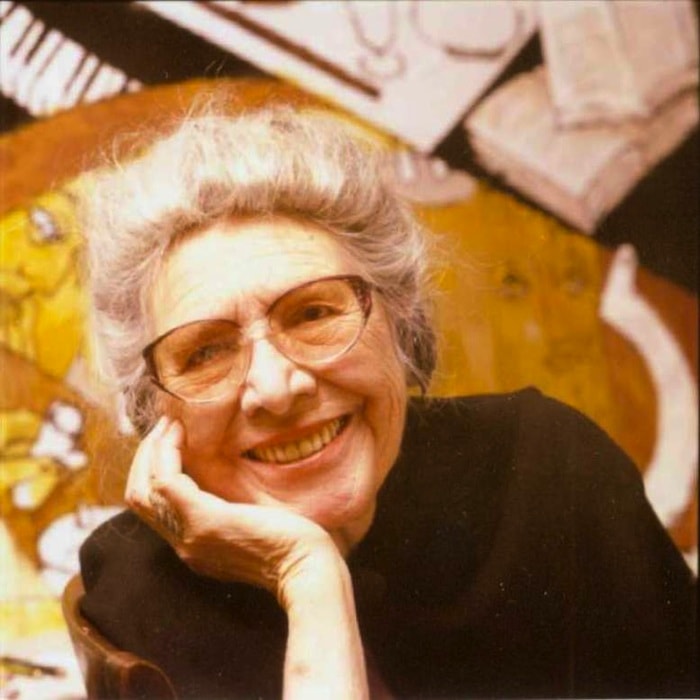

I didn’t know who Esphyr Slobodkina was the first time I saw her, but her striking appearance and demeanor caught my attention. She was dressed in an ankle-length black jumper, black stockings and Mary Jane shoes with her long white hair in a neat bun.

It was 1994 at the University of Hartford’s Hillel Theater and 83-year old Slobodkina resembled a demure turn-of-the-century lady, though her unbridled mannerisms were far from Victorian. Wearing a determined and frustrated expression, she wielded her cane like a police baton while barking clipped commands at stagehands as they wrestled a herd of five-year-old children into monkey costumes.

Engrossed by the spectacle, I immediately wished to know more about this woman.

A short time later, I applied for a job as a composer to score plays for a well-known artist and celebrated children’s author. To my surprise, the intriguing figure from the children’s theater was the person who greeted me on the evening of my audition. As I folded my lanky 6’4” frame into a chair, Esphyr Slobodkina remarked in her strong Russian accent, “Well, you’re no beauty, but you’ve got something.”

The innuendo of her audacious introduction was not lost on me; my height intimidates many people, and I recognized the parry for dominance. Thus began our professional relationship and eventual friendship—which took us from Hartford, Connecticut to Glen Head, New York, and spanned nearly eight years.

Esphyr always delighted in talking to me about her life experiences. Self-educated and well spoken, she entwined stories of history, fashion, family, and her passion for art. Her memory for detail and anecdotal ability was astonishing.

Esphyr easily recalled details of her childhood in Chelyabinsk, her family’s upheavals during the Russian Revolution, her journey to the United States, and the Great Depression. She captivated me with vivid descriptions of the artistic landscape of the 1930’s and 40’s as she shared her personal and—sometimes not too flattering—opinions about the personalities and tempers of the American Abstract Artists members and casual acquaintances from the New York art scene.

The following pages offer an intimate look at Esphyr’s personal life, as recounted in her autobiography and as told to me throughout our years together.

In the beginning, I served as her composer and personal assistant. By the end I was her caregiver, confidant, and friend. Ambitious, determined, and unwavering in her convictions, Esphyr Slobodkina was a forceful personality who actively shaped every aspect of her life and her legacy.

My hope is that these reminiscences and selections from her autobiography will offer some insight into her unique character.

* * *

Esphyr Slobodkina was born to Itta L’Vovna Agranovich Slobodkina and Solomon Aronovich Slobodkin[i] on September 22, 1908, the youngest of five children in a loving upper middle class family in Chelyabinsk, Russia. Esphyr loved her mother and father dearly, describing them as demanding yet kind people who wanted the best for their children. She attributed her own stoic temperament to the forbearance of this educated and hard-working couple.

Esphyr’s father had been a private tutor, but opportunity and ambition led to a management position with the MAZUT oil refinery. Esphyr’s mother declined a high school scholarship to pursue her passion: couture dressmaking. Both parents were driven to succeed and instilled this same ambition in Esphyr at an early age.

She often recounted the following childhood incident, which aptly captures the Slobodkin family work ethic:

One rainy morning I found myself in the dining room alone with Mother. “Mama, I am bored.” Mama pays no attention. I look at the rain-streaked window panes and begin again: “Mama, it is so boring.” Mama continues to sew a long, straight seam. “Mama, I am so bored.” Suddenly, Mama – my Mama who never, ever hit me in my whole life – turns briskly and plants a resounding slap on my pale little cheek. “Bored? Nonsense! Go find something to do, and you’ll soon stop being bored!” she roars in her magnificent mezzo-soprano. I am stunned, but I obey. I find something to do, and boredom is gone, not only for that day but forever. Never in my life have I been bored again. And if ever boredom threatens to appear, I quickly find something to keep my hands busy, and it invariably disappears. [ii]

This industrious spirit characterized the Slobokin family’s existence, but the family never lacked for joy. Esphyr’s home life in the small Siberian town was “one of governesses and cooks…and a great variety of people my father’s job and his gregarious disposition brought into our lives… Good food, plenty of music, light discreet flirtations, and much serious talk were the order of the day.”[iii]

Punctuating Esphyr’s early years were moments of tragedy and hardship. Her eldest brother, Yasha, succumbed to rheumatic fever at age 11. With great clarity, Esphyr recalled her mother’s mournful wails as Yasha lay on his deathbed. Stricken with grief, Esphyr’s mother fell ill for many months and was sent to Crimea to recuperate.

A few years later, the outbreak of the Russian Revolution presented new challenges. In 1919, due to escalating violence, Esphyr’s father decided to relocate his family. He arranged for an old hospital railroad car to be converted into passenger accommodations for five families and bribed the military for transport to Vladivostok.[iv] From there, the Slobodkins planned to catch a British ship to England and make their way to Palestine.

Shortly after arriving in Vladivostok, the Russian Empire crumbled and the ruble became valueless, rendering the Slobodkin family virtually penniless. Esphyr describes her parents’ reaction to this devastating turn of events:

One day, paler than any man I have ever seen, Father walked into our suburban apartment, sat down on a chair…and in a half-choked voice said: “We are completely wiped out…The ruble is worthless.” “What is done, is done,” was Mother’s reply. “Let’s see what can be done now.”[v]

Itta’s determined spirit and calm in the face of crisis profoundly impacted Esphyr, who would carry this sense of indomitable resolution throughout her life.

Stranded on the far edge of Russia with very little money, the family sold their few remaining jewels and moved from their luxurious apartment to a small rental house. Esphyr’s father found part-time work on the railroad and when he was paid it was only in available dry goods. Her mother began a small sewing business.

Esphyr learned the trade, demonstrating an innate flair for fashion. Although still quite young at 12 years old, she was skilled at creating embroidery designs, and clients often sought her opinions on various styles and adornments.

Tying bows, arranging loops, making up designs for the embroidery gradually became my specialty. With increasing frequency I was being called in to give my opinion of this or that detail. It was amusing because I was still so young but the ladies liked it, and I wasn’t too shy to speak my mind.[vi]

Because money was scarce in the seaport town, it was decided that Esphyr and her sister, Tamara, would relocate with their mother across the border to China to seek out wealthier clientele. The three settled in Harbin, Manchuria, in 1921.

The move coincided with the Slobodkina sisters’ progression to higher education. They attended the Second Realnoye Uchilische, a junior high school that stressed mathematics and art and prepared students for engineering degrees. Esphyr found herself drawn to architectural studies, an interest that greatly influenced her later artistic development.

Due to its strategic position on the newly completed transcontinental railway line, Harbin’s cultural development in the early 20th century was swift and expansive. By 1923, the city was immersed in all aspects of the Russian arts.

Esphyr’s world and the economy in general began to improve. As home to several thousand nationals from 33 countries, Harbin provided exposure to diverse cultures through the arts, the popular press, and theater.

Esphyr absorbed, then modified, everything she saw, attending fashion balls dressed in costumes of her own design and creating innovative accessories for garments at her mother’s shop. [Fig. 36] She excelled in her art classes, and in 1927 Esphyr graduated from high school as a well-rounded and confident young lady.

Seeking opportunity and experience, Esphyr Slobodkina left for America via steamship in January, 1928. She was 19 years old. Her brother Ronya, who had emigrated to the United States earlier, secured her passage through an art student visa. Recounting her first impressions of the New World, Esphyr writes:

As if bent upon crushing every preconceived idea I might have had about New York City, the weather provided us with a record snowfall. The city we drove through was wedding-day white, enchanted-palace quiet. To add to my happy bewilderment, the streets were broad, with no sign of the ugly skyscrapers or stone canyons everybody assured me I shall have to live with in New York. And the final, glorious surprise: The apartment…was only half a block away from the eastern rim of Central Park. I fell in love with New York — immediately, irrevocably.[vii]

Due to language confusion, Ronya inadvertently enrolled his sister in a school for missionaries. Rather than withdraw and risk deportation, Esphyr stayed registered as a day student and studied art in evening classes at the National Academy of Design (NAD). By this time, she had abandoned her intention to pursue architecture, finding the math too difficult. Later in life, however, she would revisit this childhood aspiration.

Esphyr corresponded with her mother and sister as frequently as 2 to 3 times a week during this first year in the United States. Often lengthy and detailed, Esphyr’s letters capture her emotional experience and the state of the times. Even later in life, the penned letter always remained Esphyr’s primary method of communication. Her accounts were colorful, her opinions frank, and her scathing criticisms unbridled. The following epistolary excerpt records her acerbic observations of New York life.

18 East 108 St.

New York, NY

May 30, 1928

My dear Mamochka, Papa and Tamara!

Here I am, sitting and looking at the calendar, thinking: 30th of May; a whole five months since I left home! 5 months! Almost half a year! And they flew by like a single moment. But still it seems as if I have been in New York for ages…

When spring comes to us in Harbin, every woman begins thinking of what she will wear on a bright, sunny day. Here there is no time to think of that…here they go into a store and buy everything ready-to-wear. And that is why, even in this seven-million New York, one meets the same things at every step. Here are for you the two most popular types.

- Light attire and the indispensable so-called fox. But, my God! Whatever don’t they wear under that name! The hat is at the summit—and similar beauties of nature!

- Black coat of dull silk, with a shiny stripe or some other design, and in the back…Little tales…! The many dots are to express my blind dread before the invasion of these little tales.

And so, all the women are divided into 1) women with a fox;

2) women with tails.[viii]

Through these letters, one learns that Esphyr’s first year in New York was arduous but exhilarating. She fondly remembered winning first prize for her “Pearl in a Shell” costume that she created for the annual students’ ball at the National Academy of Design (Fig. 37). It was fashioned after a Chinese pearl fisherman’s dance that she had seen at a New Year’s parade in Harbin. Esphyr recalls her dramatic entrance to the ball:

I arrived in a huge, very realistic shell, and after my brother set me down in the entrance hall (hastily departing, I must add), I minced into the ballroom with just a tiny crack to see my way. When I was sure that all attention was centered on me, I slowly opened the shell and stepped out of it to a very satisfying round of applause.[ix]

When Esphyr discussed her early life in Manhattan, I could see her vibrant younger self shining through as she spoke of the special freedom for self-expression that it offered. Skilled at dressmaking and unfettered by fear of ridicule, Esphyr designed most of her own clothing and many outfits for friends and family. These garments reflected her artistic sensibility, sometimes bordering on the avant-garde.

Her dress form was her constant companion through life, a sentinel that always stood in some corner of her bedroom near the sewing machine. During the years I lived with Esphyr, I never saw it unclothed. In spare moments, she would rework an old tuxedo or thrift shop oddity into something new and amusing to wear. Even at age 89, in preparation for a reception at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., Esphyr designed and constructed a wearable work of art complete with dress, coat, and hat.

Toward the end of her second year in New York, Esphyr was joined by her mother and sister just before the market crash of 1929, or as she so descriptively put it, “The Second Descent into Hell.”[x]

Not quite 21 years old, Esphyr faced the challenge of finding suitable lodgings for her family while working and attending school. Undaunted, she conceived the Slobodkina Real Estate Principle: “seek out the worst, most affordable apartment in the best location possible,”[xi] and manage the costs by subletting rooms and dividing the rent.

Esphyr firmly believed that compromise and sacrifice were the means to procurement and survival. Moving eleven times during her first decade in New York, she always managed to maintain a respectable address, living near Central Park, Riverside Drive, Sutton Place, or some obscure yet picturesque spot in Greenwich Village.

[Cat. 3] To earn a living, Esphyr sought numerous part-time jobs and willingly took on the most tedious tasks, such as assembling sample-making kits and selling handmade boudoir cushions and other artisanal items to New York City department stores. She recalls that “as Hoover’s prosperity persisted in hovering around the corner, good, steady jobs were more and more difficult to find.”[xii]

Finally, to her delight, she discovered that there were jobs for artists. Although not very creative pursuits, she managed to secure an income decorating lampshades, trays, and baskets and eventually found employment with the Federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) relief program.

Despite her rigorous academic and work schedule of the late 1920s and early 1930s, Esphyr maintained an active social life. In her memoirs, she wrote extensively about her intimate relationships. She describes Ilya Young as her first, and possibly only, true romantic love. Brief and bittersweet, this relationship ended in heartache.

While recovering from this devasting breakup, Esphyr met “the very short, very brilliant, and very peculiar”[xiii] Ilya Bolotowsky. Esphyr first noticed Bolotowsky in their composition class at the National Academy of Design. She was drawn to the quality of his work and asked a classmate, who turned out to be Ilya’s sister, for an introduction. “Pretty soon, the relationship narrowed down to Ilya’s regular weekly visits to our house…one could not deny one grand and rare trait of his character: he was gloriously generous in sharing his vast knowledge of art, of history, of literature, of politics.”[xiv]

When Ilya left to study in Europe, he declared his intention to marry one of the two Slobodkina sisters upon his return. Tamara was not interested, but Esphyr’s response was different. Although she was not in love with Ilya, she realized that the marriage would be practical and fruitful from an intellectual and artistic standpoint.

She reasoned: “He was the only bright, hopeful prospect. I wasn’t in love with him…After about a year…he…proved to me that it was…idiotic…to keep going to the academy just to stay in the country when, by marrying him, I could get my American citizenship and art education in one neatly wrapped package.”[xv]

Esphyr Slobodkina married Ilya Bolotowsky when she was 24 years old. Although the relationship lacked romantic passion, Ilya became her most important art teacher. Under his mentorship, Esphyr studied all the major and minor movements of the day; they visited galleries and museums, scrutinized art magazines, and attended artist meetings and rallies. Esphyr declared Ilya responsible for her early education in abstraction.

Wedged into Esphyr’s long weeks were meetings, exhibitions, and organizational events in which she participated quietly but seriously. Young innovators of American abstract art needed a voice, and she stood with them as they came together and unionized. Esphyr was especially active in the Artist’s Union, which she joined in 1934.

Like all social movements, [the Artist’s Union] brought together a great number of people. The fear of losing the hard-fought for gains pointed in one direction — even artists had to organize to protect their interests. A Union! Of course — an Artist Union. A fellow by the name of Phil Burt (or Bart) was very active. Ben Shahn and Bryson were very cheerfully dashing about organizing practically everything. Max Spivak, in spite of his stuttering, managed to be most eloquent. Even Arshile Gorky and Stuart Davis took an active interest in the early stages of the game. The dues were small, the loft we rented huge, and the meetings, at first, tremendously popular and interesting. We worked out an ambitious program of rotating exhibitions, lectures and talks by various luminaries in the arts and allied fields and, naturally, a series of fund-raising events. In the meantime, we were meeting each other, making new friends, new connections. That is how we met Gertrude (Peter) and John (Balcomb) Greene. [xvi]

Two years later, Esphyr was among the founders of the American Abstract Artists (AAA), a group that was pivotal in providing a voice for artists working non-objectively. She remained an active member of the organization for the rest of her life.

In their third year of marriage, Ilya became involved with another woman and left. Weeks later when he returned, Esphyr set strict new rules for their marriage, informing him “you can come back, but on my terms now… We live apart.” She expresses her relief at this new found freedom:

No domestic duties for me…I was rid of his family, of the kitchen and of the damn towels, socks and shirts…In accepting Ilya on these new, well defined terms…stripped of all the superficial, irritating irrelevancies of an average marriage, this union of free, yet irrevocably intertwined souls and intellects, became the true marriage — the only kind of marriage I ever recognized as a really worthwhile entanglement between a man and a woman.[xvii]

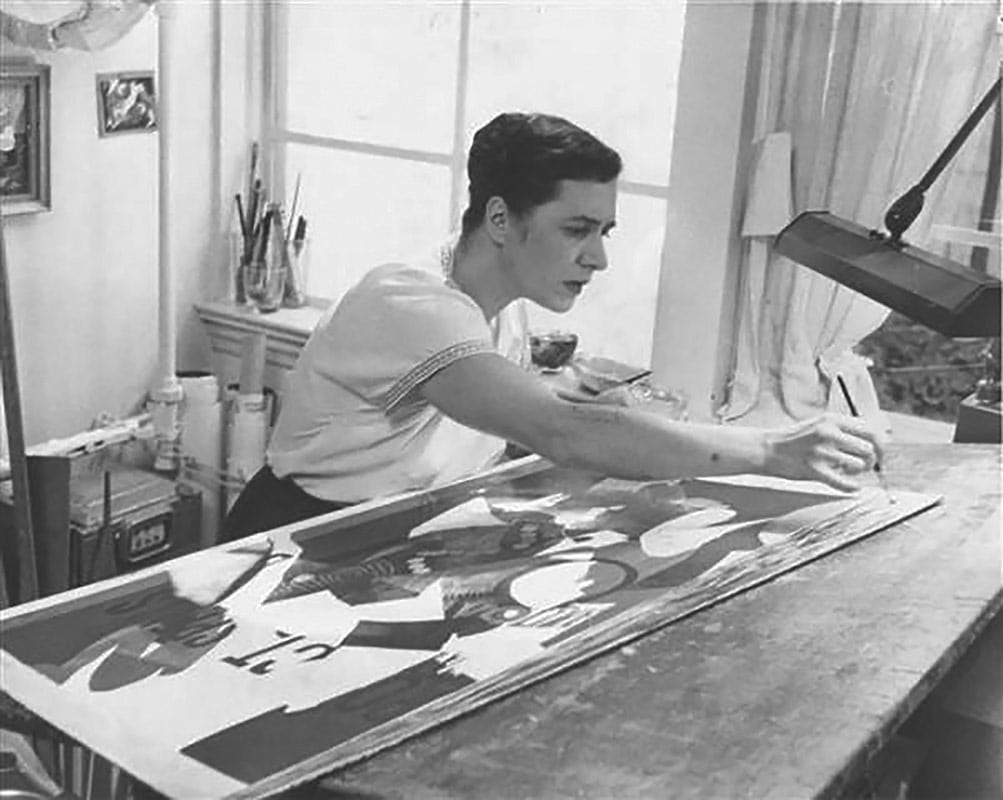

Despite these new strictures, the couple separated in 1936 and divorced in 1938, but remained close friends for a few more years. Esphyr, now unencumbered, outgrew the need for her mentor and truly matured as a painter, finding her own form of artistic expression. The winter of 1936-37 was a seminal period in her creative development. “I began to concentrate more and more seriously on painting in the abstract, though I never gave up the pleasure of the more emotional, more direct self-expression in still life and landscape painting. The immediate events…called for concentration, for rapid development and achievement in the abstract field.”[xviii]

As she continued to mature artistically, Esphyr simultaneously sought work that would provide immediate income. In 1937, at age 28, Esphyr accepted a job in Paterson, New Jersey, with an interesting new firm experimenting with a secret, revolutionary method of textile printing called polychrome. The job required artistic ability in fabric design and the capability to hire and fire staff.

My peculiar inclination towards ornamental design and the always evident ability to produce a firm, well-balanced composition were just what the job needed. It was messy, rather dirty and hard work but I took to it like a duck to water. The fantastic possibilities of the darn thing were mind-boggling.[xix]

Esphyr demanded $15 a week (an exorbitant salary for a woman at that time) and got it. The lengthy commute from Manhattan made her late for many of the artists’ meetings, but the job brought financial security for nearly three years.

In this same year Esphyr met Johnny J., a love interest she described as “a penny in a dime suit… he was always there seemingly intent on nothing else but amusing me.”[xx]

Associated with various New York socialites and literati, Johnny presented Esphyr with a life-changing opportunity when he introduced her to children’s book author, Margaret Wise Brown. In preparation for an interview with Brown, Esphyr considered her artistic options and settled on innovative collage illustrations of her own children’s book called Mary and the Poodies. Brown and her publisher found Esphyr’s abstract collage style refreshing and new, and subsequently hired her to illustrate The Little Fireman (1938). The book was a critical and popular success.

The outcome of this first literary enterprise was an association that blossomed into friendship. Keen on social networking and confident of her rightful place in society, Esphyr was delighted to summer at Margaret’s cottage in Maine in 1939 and 1940 where she would vacation with the high-society guests that frequented the island. Slobodkina captures the bohemian and sometimes risqué attitude that permeated island life as she recalls an island-hopping excursion from the main cottage:

We had an amusing time playing out a charade of harem girls, minus the master. We sun-bathed, swam au naturel and took nude pictures, which we had great difficulty in having printed. Too bad they were not in color — we must have made quite a pleasing assortment beginning with blond Betty, to Strawberry-red Beulah, brown-haired me and jet-black, white-skinned Leslie.[xxi]

At mealtimes, philosophical and thought-provoking discussions were spearheaded by Brown. Esphyr and Margaret were like-minded in their opinionated temperaments, if not always their views. A mutual respect developed, and Margaret embraced Esphyr as her confidant.

Life with Margaret was exhilarating, deeply sentimental, enlightening, and all too brief. Their friendship and book collaboration continued until Margaret’s untimely death in 1952. Esphyr eventually penned and illustrated fifteen of her own children’s books including the classic Caps for Sale.

Just as Esphyr’s illustration career began to take off, tragedy struck when her father unexpectedly passed away. It was 1938. Once again, Esphyr faced the task of caring for her mother. “The death of my father brought great changes into my life. As the only unattached child, I was quite naturally expected to pool my resources with my mother’s and to provide a home, consolation, and companionship for my bereaved parent.”[xxii]

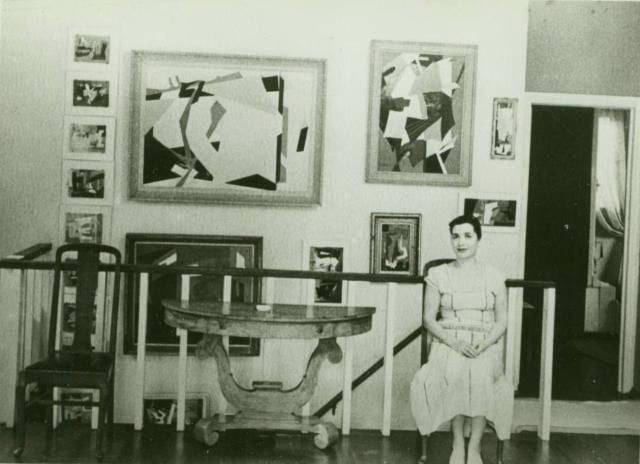

Mother and daughter moved into a “charming apartment on the third floor of a brownstone building on 60th Street between Park and Lexington.” After a period of grieving, Esphyr began hosting gatherings in her new space and soon became chairman of the American Abstract Artists entertainment committee. At these parties one could find art world luminaries and various figures from the publishing world.

At first, our guests were our personal and business friends – Margaret [Wise Brown], Charles Shaw, Suzy and George [L.K.] Morris, Gallatin, and my editors of the moment were all among our visitors. When in the late thirties and early forties the first waves of intellectual refugees from Nazi Germany and Austria began to reach New York, the American Abstract Artists…decided to welcome them into the artists’ community. I was unanimously elected as chairman of the entertainment committee…In our Sixtieth Street apartment we gave parties: for as many as one hundred people with a lavish buffet supper and an abstract movie by Man Ray for entertainment; a more intimate reception and an afternoon tea for Mondrian; and a few little dinners for visiting celebrities and their wives. It was fun, it was exciting, and I suppose it did no harm to my career.[xxiii]

Esphyr continued to produce and exhibit art at a feverish pace, but soon found herself making time for a new romance. At a 1942 American Abstract Artists exhibition, she met her second husband, William L. Urquhart. Drawn to his intellect, good looks, and old-fashioned manners, he became a friend, employer, and secret lover. After the death of William’s wife, Esphyr and he were married. Tragically, William, 20 years Esphyr’s senior, died in their third year of marriage in 1963.

With the income from her various jobs, small royalties from the books, an occasional sale of art, and still using the Slobodkina Real Estate Principle, Esphyr sublet her 60th Street apartment and purchased her first home in Great Neck, New York in 1948. At age 40, she was finally afforded the opportunity to experiment with architectural and interior design.

The Great Neck residence was an unusual structure, fitted into the side of a hill. Armed with a vision to improve the allotment of studio space, Esphyr hired an open-minded contractor willing to work with her blueprint. For two years she prevailed upon the town for permission to execute her plans.

Eventually, Esphyr begrudgingly compromised her design, and the project was allowed to begin. The contractor enclosed half of an exterior concrete slab that ran along the backside of the building, moving windows, doors, and a staircase to achieve the desired results. The newly enclosed space became a 17 x 25 foot studio – a large, well-lit room that enabled Esphyr to produce larger-scale artworks. Interior renovations were done almost exclusively by Esphyr, including all floor staining. She covered the walls with vibrant paints such as rich plum, or deep green, and even reconstructed the furniture to suit her aesthetic sensibility.

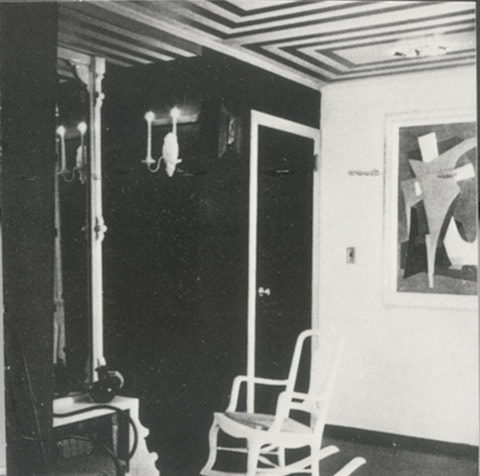

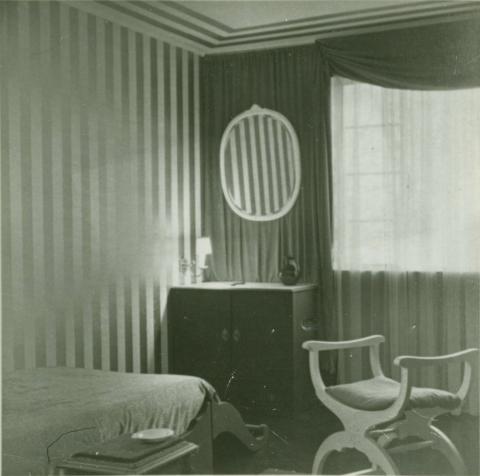

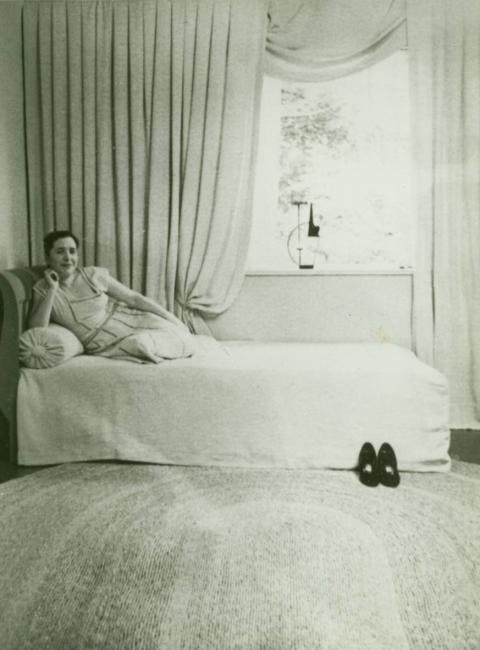

Slobodkina’s elegantly decorated bedroom in her Great Neck house, ca. 1950. Friends often commented that Slobodkina would “Esphyrize” every space she inhabited. Indeed, the artist always remodeled, redesigned, and rearranged her environment to suit her particular aesthetic sensibilities. Rather than purchase expensive furniture,

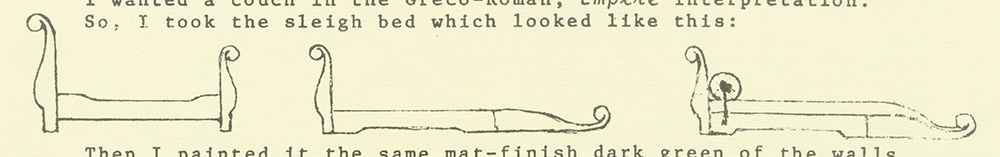

I went quite exotic…Some of the walls, the door and the floor were painted dark, bluish green. The west wall, the ceiling, the trim and part of the east wall with its rather large picture window, were painted white. The remaining walls were covered in a striking paper of broad gold-and-white stripe – very stark, yet very Empire. A border of the same paper ran around the edge of the ceiling in two oblongs with perfectly mitered corners…all the furniture, including a tremendously tall pier glass mirror, was painted white. Longing for a fireplace I could not afford, I built an artificial one under the mirror, with the help of some left-over bricks and one of the office electric heaters. Most of the furniture was white, but not the bed. Now, the bed was a fun piece…I bought a really old-fashioned sleigh bed…and since my bedroom was long and narrow, the bed had to be cut down. I did not want just a bed-I wanted a couch in the Greco-Roman, Empire interpretation. So I took the sleigh bed which looked like this:

Then I painted it the same mat-finish dark green of the walls, gave it a gold moiré bedspread and a round tasseled bolster, placed the…white fur rug alongside it, and voila! – a real Empire bit…The same gold moiré was used for the drapery which framed the sheer white curtains.[xxiv]

Bolstered by the success of the renovations, Esphyr designed and oversaw the construction of a house for Tamara in 1967. Still standing today, the house echoes the clean geometries and formal simplicity of her paintings.

Esphyr and her mother lived in Great Neck for 30 years.

Exterior and interior views of the house that Slobodkina designed for her sister in Great Neck, New York, ca. 1972.

Tamara eventually moved to Florida, but when her husband died the family was once again reunited. In 1979, Esphyr sold her house and moved with her mother to Hallandale, Florida to be near her grieving sister.

Esphyr soon became an active participant in the Florida arts and cultural scene. She exhibited her art, lectured on her children’s books, and taught doll-making classes, one of her many pastimes.

While in Hallandale, just months before her mother passed away at age 98, Esphyr had an exhibition at the Hollywood Art Museum. She placed one of her mother’s paintings in the show. (Her mother had begun studying art under her daughter’s tutelage 23 years before.) The inscription that Esphyr placed by the painting attests to their special relationship: “She was my best student in art, and my best teacher in life.”

The years surrounding Esphyr’s move to Florida were among her most emotionally challenging. While still grieving the death of her husband and mother, Esphyr lost her brother, a favorite cousin, her aunt, and long-time friends George L.K. Morris, Suzy Frelinghuysen, and Alice Mason among others.

To cope with a deep and mounting depression, Esphyr began compiling her Notes for a Biographer. This 1,100-page autobiography, which Esphyr painstakingly retyped many times, offers a chronicle of the Slobodkin family from the late 19th century through 1983.

It includes vivid depictions of the mood of each decade through Esphyr’s artistic eye, correspondence containing intimate commentary on friends, lovers, and contemporaries, and tidbits of stories, gossip, and recipes. In typical fashion, Esphyr dealt with her emotional crisis through the panacea of work.

By the end of 1991, Esphyr Slobodkina, 83, and Tamara, 85, relocated to West Hartford, Connecticut so that Esphyr could oversee the construction of the Slobodkina/Urquhart Children’s Reading Room – a building she funded and designed for the University of Hartford (William’s alma mater).

Esphyr decorated the interior with 26 paper and cloth collage murals that recreate illustrations from her first children’s book, Mary and the Poodies. During this period, Esphyr began to think about her legacy, actively seeking homes for “her babies” (as she referred to her artworks) that were not yet with collectors or museums. Negotiations began with the Hillwood Art Museum and the Heckscher Museum of Art, both in New York. Each institution now owns a substantial collection of her art and archives.

Esphyr revisited the Slobodkina Real Estate Principle one last time when she, Tamara, and I moved to a house in Glen Head, New York in January 1999. There, Esphyr established the non-profit Slobodkina Foundation, an organization that would offer educational children’s programs, art tours, and archival resources for researchers.

Esphyr lived her remaining years freely and fully, hosting numerous parties and overnight get-togethers with close friends, and entertaining family and the hundreds of guests who came to the Slobodkina House to meet the legend and enjoy her art.

Esphyr continued to produce art until shortly before her death on July 22, 2002. She is remembered for her unconventional artistry and independent disposition, which places her ineluctably among the female pioneers of the 20th century.

About the Author

In 1995, while studying at the University of Hartford, Ann Marie Mulhearn Sayer began an association with artist, author, illustrator Esphyr Slobodkina. Originally hired to produce musical versions of Slobodkina’s children’s books, Sayer ultimately served as Slobodkina’s personal assistant from January 1996 to July 2002. Although separated in age by over forty years, the women soon became fast friends. Sayer and Slobodkina found they shared a synchronicity in thinking: an out-of- the box approach to creative endeavors and problem solving.

It was Slobodkina’s wish that after her death, Sayer continue her work and keep Slobodkina’s art, books, and illustrations in the public eye for future generations to enjoy. In the year 2000, Esphyr Slobodkina formed the Slobodkina Foundation. Ann Marie Mulhearn Sayer serves as president of the Slobodkina Foundation and has been administrating, cataloging, and exhibiting Slobodkina’s fine art, children’s books, textiles, and publications for over twenty years.

Endnotes

1 The letter “a” is added to the Russian surname when using the feminine form.

2 Esphyr Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 1 (Great Neck, New York: Urquhart-Slobodkina, 1976), 55.

3 Esphyr Slobodkina, “Esphyr Slobodkina,” in Something about the Author Autobiography Series, vol. 8, Joyce Nakamura, ed. (Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research, Inc., 1989), 278.

4 Begun in 1891, the Trans-Siberian Railroad runs from Moscow through the Siberian steppes to the pacific port of Vladivostok and covers 5,778 miles. Direct railway connection between Chelyabinsk and the pacific coast was established in October 1916. During the war, nearly all commercial rail traffic was halted to allow uninterrupted military equipment transport.

5 Notes for a Biographer, vol. I, 117.

6 Ibid., 165.

7 Esphyr Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 2 (Great Neck, New York: Urquhart-Slobodkina, 1980), 231.

8 Ibid., 235-237.

9 Ibid., 259.

10 “Esphyr Slobodkina,” 288.

11 Notes for a Biographer, vol. II, 283-84.

12 Ibid., 296.

13 “Esphyr Slobodkina,” 290.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Notes for a Biographer, vol. II, 371-372.

17 Ibid., 397-398.

18 Ibid., 426.

19 Notes for a Biographer, vol. II, 369

20 Ibid., 412

21 Ibid., 554.

22 Ibid., 456.

23 “Esph23yr Slobodkina,” 293.

24 Esphyr Slobodkina, Notes for a Biographer, vol. 3 (Great Neck, New York: Urquhart-Slobodkina, 1983), 768-9.